“Men with hands and no head, and men with head and no hands, are equally out of place in the modern community.”

Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence

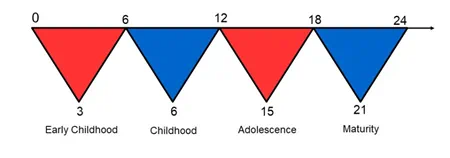

In two previous articles, we discussed the Planes of Development as the bases for the Montessori three-year multi-age classrooms. Specifically, we looked at how the prepared environment of the Early Childhood and Elementary classrooms meets the developmental needs of children by reflecting the sensitive periods of the corresponding planes.

The focus of this article is the third plane and Erdkinder—Montessori’s vision for meeting the unique needs of the Secondary student.

What are the needs and characteristics of the adolescent?

Montessori articulated her vision for Secondary education in From Childhood to Adolescence some 75 years ago. Writing against the backdrop of postwar society and rapid advancement in new technologies, Montessori argued that the Secondary schools were “adapted neither to the needs of adolescents nor to the time in which we live” (1948/2007). And although the times have changed significantly, the unique developmental characteristics of the adolescent remain the same:

- Physical: Adolescents experience a period of tremendous physical and neurological growth.

- Emotional: They experience self-awareness and self-criticism, emotional ups and downs, and egocentrism. They feel an increased desire for autonomy, along with a susceptibility to peer pressure. It is a time characterized by a tendency toward courage and creativity.

- Social: Adolescents seek solidarity with peers and crave greater independence from adults as they establish their own identity. They are concerned with human welfare and dignity, and may exhibit novelty-seeking and risk-taking behaviors as a response to a tendency to express courage and creativity.

- Cognitive: Adolescents are critical thinkers who persistently ask “why.” They are creative, and have the ability to reason and debate.

Montessori wrote that these characteristics would be best addressed in a community setting where adolescents were well removed—figuratively and literally—from the traditional classroom of lecture-based instruction, as well as from their parents/guardians. As she puts it in Citizen of the World (2019, 40):

The child should no longer be restricted to the environment of the school … nor be so close to the family from which he depends financially; he wants ‘to live’ society. He should go farther away.

From this premise, Montessori developed her vision of Erdkinder.

What is Erdkinder?

Literally, Erdkinder is translated as “earth children” or “children of the land.” The name reflects Montessori’s belief that the ideal setting of a Secondary program would be a residential farm where a small group of adolescents (12 – 15 years) and adults (teachers and mentors) live and work together, with the farm providing purpose and meaning to the community:

[The farm] is an integral part of our curriculum and also provides practical life experience in critical thinking and problem solving. Work with the animals and the land encourages the adolescents to cultivate a sense of empathy and think critically about the sustainable practices that impact our world. Their work also promotes perseverance and daily habits of care for the environment. This responsibility fosters an awareness of the part they play in the well being of the greater community.

“We have called these children the ‘Erdkinder,’” Montessori wrote, “because they are [also] learning about civilization through its origin in agriculture” (1948/2007). Studying the progress of civilization through the lens of the advancement of technology provides meaningful work for both the hands and the intellect, equally important. Academic subjects are directly integrated with projects related to the upkeep of the farm and residence. The adolescent may participate in:

- building and construction

- preparing and managing gardens

- animal husbandry

- land stewardship

- utilization and maintenance of farm equipment

- cooking and meal preparation

- entrepreneurship

The farm, in essence, is the prepared environment for the adolescent, wherein “students are given the unique opportunity to prepare an environment for themselves:”

The land-based Montessori middle school gives adolescents what they need most — the space from which they are invited to create their own identity. They now use the “freedom through discipline” that they have learned through all the other Montessori levels to begin to understand themselves. With the land as their classroom they begin to ask the questions of themselves, “What can I do? What are my strengths? What is my place in adult society?”

In this way, academics are integrated with personal interest work. In addition to their regular academic subjects, [students] are given many choices, and with the guidance and encouragement of adults, together with the knowledge acquired through academic studies, they engage in a range of activities during this time of self-exploration.

Beyond academics: How does the Erdkinder program meet the personal and social needs of the adolescent?

The adolescent on the farm is engaged in a variety of activities and projects that:

- are community based. As a member of the community, the individual’s contribution is recognized as important. Cooperation, collaboration, and group problem solving are the social-psychological foundations of the community. The adolescent learns to live and work with others, fulfilling the need to belong to and be accepted by a group.

- help the adolescent form a personal identity. Through their contributions to the community and their pursuit of personal interest projects, the adolescent begins to explore the potential role(s) they could occupy as adults. (See Erikson’s psycho-social stages of development—identity vs. role confusion.)

- require the mentorship of adults. By working closely with adults with a range of expertise, the adolescent forges strong and meaningful relationships beyond their immediate family, addressing the need for independence from one’s parents.

- provide opportunities for self-expression. A variety of choices involving creative, performing, and vocational arts; sports; public speaking; and other meaningful forms of personal expression provide avenues to explore identity and assert individuality.

- promote entrepreneurship and economic independence. By mak[ing] collective economic decisions while learning budgeting, management, sales and labor in conjunction with [the] farm, the adolescent learns about economics in the real world while promoting the economic activity of the community.

How feasible is implementation of an Erdkinder program?

A small group of Montessori leaders met in the early 1970s to establish the Erdkinder Consortium, with the aim of developing “an American Montessori secondary model” based on Montessori’s vision. The group came to the consensus that urban-based schools should be encouraged to develop modified Secondary programs, given the lack of land and other resources required for a farm-based learning community.

While a farm- or land-based residential program is beyond the financial or logistical range of most contemporary Montessori schools, many schools have developed highly successful Secondary programs that balance academics with physical activities, indoor studies with outdoor studies—work for the head and work for the hand (see one example here). The same article outlines what a more viable but still outstanding secondary program might look like.

Montessori did not live to see the full implementation of her vision for the adolescent’s education, but dedicated practitioners have endeavored to put in place high quality Secondary programs—farm based, land based, classroom based, or blended—that meet the unique needs of the adolescent.

One last look at the image of Montessori’s model of development reminds us that similarities exist between the first and third planes—profound physical change, for one. Another striking parallel is the young child’s and adolescent’s resolute drive toward independence. As Montessori wrote in From Childhood to Adolescence (p. 67):

Independence, in the case of the adolescents, has to be acquired on a different plane, for theirs is the economic independence in the field of society. Here, too, the principle of “Help me to do it alone!” ought to be applied.

A community-centered environment where adolescents live and work independently, take on adult-like responsibilities, and engage in business enterprises of production and exchange, fulfills the need for social and economic independence characteristic of the third plane of development. While the farm—where academics are integrated with life and physical work— may be the ideal prepared environment for the adolescent’s education, many modified Secondary programs are in place that serve, through a variety of approaches, the unique needs of the middle-school student.

Other References

Montessori, Maria. From Childhood to Adolescence. New York: Schocken Books, [1948] 1973.

Montessori, Maria. Citizen of the World. Netherlands: Montessori Pierson Publishing Company, 2019.