“I have found that in his development, the child passes through certain phases, each of which has its own particular needs. The characteristics of each are so different that the passages from one phase to the other have been described by certain psychologists as ‘rebirths’.”

—Maria Montessori, Citizen of the World, p. 32

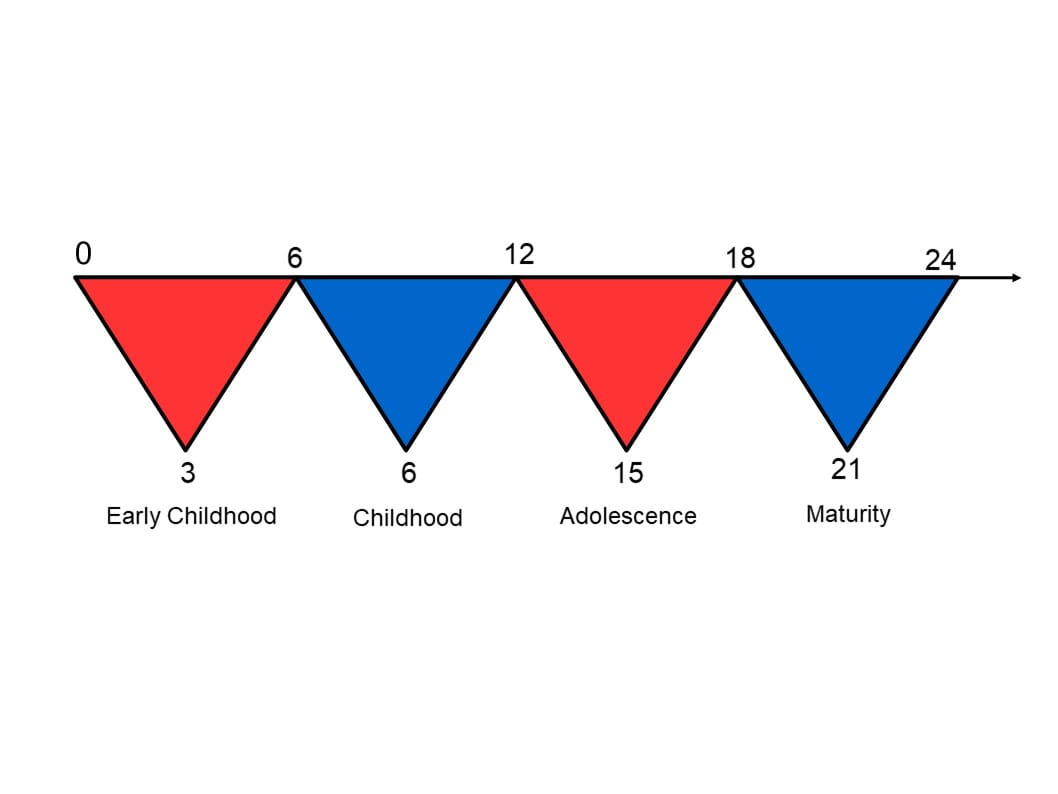

One of the most foundational features of Montessori education is the three-year multi-age programs. These configurations are not arbitrary, but are based on the planes of development, or four distinct periods of growth: 0 – 6 years; 6 – 12 years; 12 – 18 years; and 18 – 24 years. Maria Montessori (and other developmental theorists, like Jean Piaget and Erik Erikson) confirmed that children develop through a series of observable stages, each with specific needs and predispositions—cognitive, social, physical, moral, and emotional. Montessori’s developmental model is represented in the following illustration:

The red periods represent rapid growth and hormonally-driven changes (think of infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and adolescents); the blue periods represent quieter, more stable periods of development. In Piagetian terms, the red periods might be identified as disequilibrium, and the blue periods as equilibrium. In fact, Montessori wrote (1948) of the second plane that the child “is in a state of health, strength, and assured stability,” and of the third plane, that “it is a period of so much change as to remind one of the first” (1949).

Each plane is divided into two sub-planes, on which the Montessori multi-age classrooms are based:

- First Plane

- 0 – 3 years (Infant/Toddler)

- 3 – 6 years (Early Childhood)

- Second Plane

- 6 – 9 years (Lower Elementary)

- 9 – 12 years (Upper Elementary)

- Third Plane

- 12 – 15 years (Middle School)

- 15 – 18 years (High School)

In Montessori’s words (2019):

With regard to the child, education should correspond to these stages, so that instead of dividing the schools into nursery, primary, secondary, and university, we should divide education in[to] planes, and each of these should correspond to the phase the developing individual is going through.

A fourth plane, 18 – 24 years, is not associated with Montessori classrooms, but is integral to Montessori’s developmental model. This is a time of transition from adolescence to young adulthood. The first sub-plane, 18 – 21 years, often represents the college-university years, while during the second sub-plane, 21 – 24 years, young adults construct an understanding of the self and seek to know their place in the world.

It should be noted that Montessori’s developmental model does not end at twenty-four years. While she writes little about lifespan development, images of her developmental model often depict an arrow at the twenty-four-year mark, indicating that development continues. This is consistent with the psychosocial model of development of psychoanalyst Erik Erikson (who, incidentally, earned a certificate in Montessori Education).

The “phases” that Montessori refers to in the above quotation are known as sensitive periods (or critical periods in contemporary neuroscience) and can be defined as:

A critical time during human development when the child is biologically ready and receptive to acquiring a specific skill or ability—such as the use of language or a sense of order—and is therefore particularly sensitive to stimuli that promote the development of that skill.

Put differently, children and adolescents have a natural disposition toward certain activities and skills at, roughly, the age periods delineated above. Montessori teachers are trained to observe children and adolescents so they can prepare the environment to meet their developmental needs with appropriate materials. Corresponding to the materials are three-year curricula oriented to the inherent characteristics of each plane.

The curriculum is spiral-sequential and integrated across all curricular areas, and by completing the three-year cycle in an environment specifically designed to address their developmental needs—whether in the Early Childhood, Elementary, or Secondary program—the child’s possibilities for working toward their potential are maximized.

In this first installment, we explore the sensitive periods of the child in the Early Childhood program and how they are addressed in the classroom. Part Two will examine the same for the Elementary program, and Part Three will focus on the third plane and Montessori’s vision for the adolescent–Erdkinder (Child of the Earth).

The First Plane of Development (Early Childhood)

Montessori refers to the first-plane child as being endowed with an absorbent mind; that is, they learn spontaneously by consciously or unconsciously absorbing elements in the environment. In Montessori’s words, “The only thing the absorbent mind needs is the life of the individual; give him life and an environment and he will absorb all that is in it” (1946).

The environment to which she refers is the prepared environment—the curriculum, materials, and activities which reflect the sensitive periods of the first-plane child. These include:

- order (what is alike and what is different)

- language (letter recognition and vocabulary)

- refinement of movement (coordination)

- refinement of the senses (discrimination of sensory stimuli)

- concentration and repetition (toward achieving a goal)

- grace and courtesy (social skills)

- independence (physical autonomy)

The environment of the Early Childhood classroom fulfills the young child’s needs through a series of Sensorial, Language, Math, Cultural, and Science materials, as well as Practical Life activities. Materials like the Knobbed Cylinders, Pink Tower, and Red Rods lead to refinement of both movement and of the senses, especially the visual and tactile senses and, more specifically, the discrimination of changing dimensions.

As these materials require seriation skills, the child’s sense of order is also at work, indirectly preparing them for future work in mathematics. Once the mathematical mind has been thus primed, the child is introduced to beginning math materials such as the Number Rods, the Spindle Box, Numerals and Counters, and more, and they embark on the study of mathematics proper.

Additional sensorial materials engage other senses; for example, the Smelling Bottles strengthen olfactory discrimination, and the Bells and Tone Bars promote auditory discrimination. Since the child works alone after the initial presentation on the sensorial materials, they are also practicing independence. The teacher does not intervene unless the child asks for help, leading to the child’s confidence in their own abilities. Finally, each of the sensorial materials (including those not listed above) requires concentration on the part of the child, which is essential to success in their future academic work.

The first-plane child also learns a great deal of new vocabulary through their use of the sensorial materials, which, along with Practical Life experiences, also provide indirect preparation for writing (holding a pencil) as the child handles the small pieces using a pincer grip. Other materials, however, are more directly aimed at letter recognition, writing, and reading. These include (among others):

- the Sandpaper Letters

- the Sand Tray

- the Metal Insets

- the Movable Alphabet

- chalkboards for writing

- phonetic and phonogram objects, cards, booklets

- realistic books

The Early Childhood Practical Life activities (such as table washing, food preparation, flower arranging) all require motor control, concentration, and independence. As such, they contribute to the child’s drive toward physical autonomy, and toward exerting themselves in their surroundings.

Other Practical Life activities utilize social rather than physical skills: saying “please,” “thank you,” and “excuse me;” waiting one’s turn; introducing oneself; asking for and offering help. Practicing these skills appeals to the young child’s sensitivity to grace and courtesy, learning and practicing social skills that they will use as they “adapt to life in a group … both in and out of school.”

We said elsewhere that grace, courtesy, and cooperation give the child the necessary tools for positive social interactions, while order, coordination, concentration, and independence are essential to learning and academic success. By preparing the Early Childhood environment with materials and activities that reflect the corresponding sensitive periods of the first plane, the child’s innate developmental needs are fulfilled at the same time they are learning language, math, and social skills and receiving indirect preparation for future academics.

Everything in the Early Childhood prepared environment is designed around the sensitive periods of the three-to-six-year-old child. It should be no surprise then, when walking into an Early Childhood classroom, to see children purposefully engaged in activities in which they exhibit orderliness, coordination, concentration, and independence; exert themselves in their environment; and carry out harmonious social exchanges with those around them. This is the result of a well-prepared environment in tune with the drives, needs, and inclinations of the child.

References

Montessori, Maria. The 1946 London Lectures. Netherlands: Montessori Pierson Publishing Company, [1946] 2012.

Montessori, Maria. To Educate the Human Potential. Oxford: Clio, [1948] 1989.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind. New York: Dell Publishing Co., [1949] 1969.

Montessori, Maria. Citizen of the World. Netherlands: Montessori Pierson Publishing Company, 2019.