The next period goes from six to twelve. It is a period of growth unaccompanied by other change. The child is calm and happy. Mentally, he is in a state of health, strength, and assured stability.

—Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, p. 18

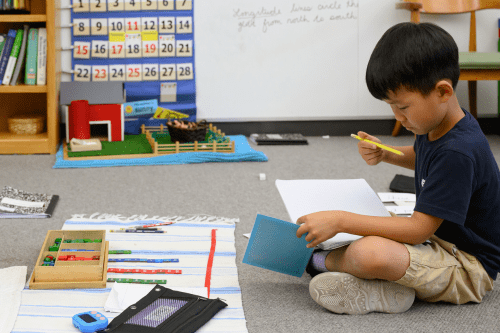

In Part 1 of our series on the planes of development and sensitive periods, we introduced and defined these core concepts of Montessori education as the rationale for the multi-age classroom, which itself is foundational to Montessori philosophy and pedagogy. We reviewed the sensitive periods of the first-plane child and how the prepared environment of the Early Childhood classroom reflects their specific needs and predispositions with a curriculum and materials that match the inner development of the young child. The present article focuses on the same for the Elementary program.

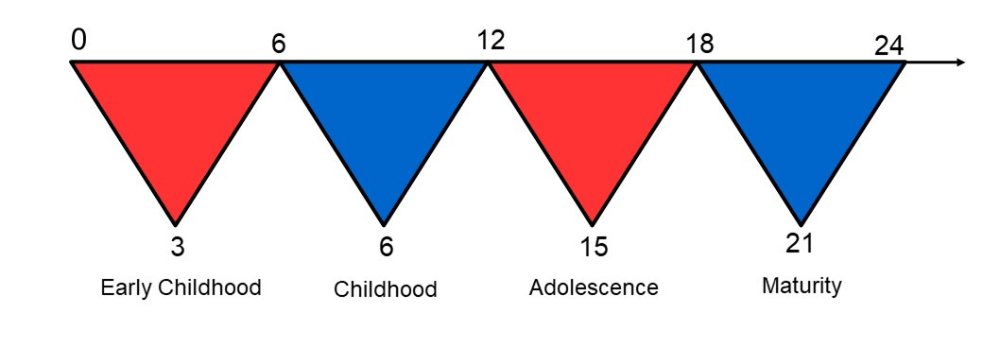

To reiterate, we defined the planes of development as four distinct periods, with the red areas characterizing times of rapid growth and profound change, while the blue areas represent more quiet, stable periods where growth occurs, but with relatively little change.

Each of the periods is divided into three-year sub-planes, which are the bases of each level of the Montessori program:

First Plane

- 0 – 3 Years (Infant & Toddler)

- 3 – 6 Years (Early Childhood)

Second Plane

- 6 – 9 Years (Lower Elementary)

- 9 – 12 Years (Upper Elementary)

Third Plane

- 12 – 15 Years (Middle School)

- 16 – 18 Years (High School)

The Second Plane of Development (Lower & Upper Elementary)

Montessori writes about the absorbent mind as a defining characteristic of the first-plane child. This means that the child in the first plane takes in impressions from the environment and mentally records them. The 6 – 12 year-old child, on the other hand, reflects and reasons about their observations. Montessori shares the following anecdote, comparing the absorbent mind of the first-plane child with the reasoning mind of the second-plane child (2019):

In a school we were carrying out experiments in biology; there was an aquarium that was accessible to children from three to nine years. One morning the fish were all dead. The little ones, struck by this fact, ran to every newcomer to announce that “the fishes are dead,” then ran back to their former occupation. The older children stood quietly around the aquarium saying: “Why are the fish dead? Why? Why do things happen? How do they come about?

This anecdote illustrates the second-plane child’s predisposition toward reasoning and abstract thinking, which we discuss below. The child in this plane is also in the sensitive period for:

- Imagination

- Social order

- Morality and ethics

- A global perspective

Reasoning and Abstract Thinking

As the anecdote above illustrates, the older child is interested in the reasons for things. They are in the process of consolidating their knowledge and making connections between the ideas and impressions absorbed during the first plane. In a previous article, we shared Montessori’s analogy that it is as though the younger child is busy collecting books, and when they reach Elementary, they discover they have a library. Through their emerging power of rational thinking, the child puts order to their library of books by categorizing and classifying information. To this end, an extensive range of lessons and activities—from astronomy to zoology—are available to arouse the child’s imagination and promote inquiry and investigation.

This switch to reasoning things out involves abstract thinking, which is facilitated by the spiral curriculum and may be best illustrated with the Elementary math materials. The materials are designed to be used in a sequence, from very concrete to more and more abstract, until the child learns the algorithms for solving different kinds of math problems. These algorithms are not taught by the teacher, but are discovered by the child as a series of steps they have taken with the materials. In this way, they do not merely memorize an algorithm, but, because of the embodiment of the steps in the materials, they learn to understand the function of and reason for each step. Reason and abstract thinking also overlap with the other predispositions of the second plane.

Imagination

The five Great Lessons (described here) epitomize how the curriculum is designed to appeal to the imagination of the second-plane child. The lessons are meant to elicit wonder about a variety of topics from all areas of the curriculum, and to help the child conceptualize such big ideas as the formation of the universe, early life on Earth, the development of humans, and the history of writing and numbers. Since the child cannot experience these big ideas firsthand, the lessons are presented in a way that kindles their imagination and fuels curiosity. Montessori wrote of the second-plane child in To Educate the Human Potential:

Knowledge can be best given where there is eagerness to learn, so this is the period when the seeds of everything can be sown, the child’s mind being like a fertile field, ready to receive what will germinate into culture.

The imagination, then, is a powerful tool with which the child can grasp abstract concepts that are otherwise beyond the realm of their experience. As mentioned above, there is overlap between imagination and reasoning during this time of development. From the ideas presented in the Great Lessons, the child selects and explores topics of personal interest, asking questions and looking for answers—inquiry and investigation. By way of example, after a lesson on the development of life on Earth, a child might find the idea of beneficial bacteria intriguing, then question and investigate why some bacteria cause illness while others are essential to life on Earth—such as cyanobacteria, an essential component of photosynthesis and the oxygenation of our atmosphere.

Social Order, Morality and Ethics, and Global Perspective

The Elementary-age child has developed a new awareness of social order, and the Montessori multi-age classroom increases the child’s range of sociability. New lessons come along and interests shift over time. Dynamic peer groups within a three-year age range increase the chances that the child will find another, or others, who share their interests and skill level with whom to work.

With increased social awareness, the second-plane child is also concerned with rules and what’s fair; that is, their social sensitivity is closely tied to their emerging sense of morality and ethics. The child’s interest in social order necessarily includes the rules that govern social groups; and following the rules is governed by their developing awareness of right and wrong, of perceived justice and fairness. We begin to see in the second-plane child “the beginning of an orientation toward moral questions, toward the judgment of acts” (Montessori 1949).

This may manifest with the six-year-old in the form of tattling, which is one way of checking in with an adult that they understand the rules correctly. Older children may begin to recognize racial and economic injustice, for example, and other instances of bias, prejudice, and disparity in their own communities and even in their own classrooms. The degree to which anti-bias, antiracist (ABAR) principles are in place and inform the dynamics in the classroom will play a large part in determining how successfully children navigate related questions and issues that may arise.

Eventually, the older child will begin to look beyond the classroom and playground—toward the rules that govern society at large, and at other worldwide problems such as environmental degradation and human rights issues. In this way, their developing ethics coincide with and inform their emerging global perspective.

Upper Elementary (UE) children, especially, begin to take an interest in global issues and are often struck, even outraged, by injustices they are only now, developmentally speaking, becoming aware of. Often, they want to take action to help in some way. They may initiate a fundraiser, for example, in order to contribute to a freshwater project in a developing country. This is also the age when some children decide to become vegetarian, as they begin to ponder the rights of animals. Others may make a connection between the consumption of animal products and the environmental impacts of raising and transporting these products.

The Montessori Elementary cultural curriculum appeals to this period of global awareness through history, geography, language, and science lessons in which children explore not only their own culture, but others as well. For the curriculum to be relevant and meaningful, however, Montessori educators are charged with ensuring that their classroom materials and lessons are culturally representative and historically accurate so that all children feel seen and heard.

The above examples illustrate how the individual threads of the child’s development during the second plane are entwined in a finely woven curriculum that provides the child with a range of personalized learning opportunities. Not only is the child able to explore topics of their own interest, but they engage those intellectual faculties to which they are developmentally predisposed along the way. The well-prepared Elementary environment gives the child the tools to imagine big ideas, ask big questions, and extend their thinking beyond the classroom to the wider world.

In our final installment of this series, we’ll examine the Erdkinder program—Montessori’s vision for the adolescent—and how it meets the unique needs of the Secondary student.

References

Montessori, Maria. To Educate the Human Potential. Oxford: Clio, [1948] 1989.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind. New York: Dell Publishing Co., [1949] 1969.

Montessori, Maria. Citizen of the World. Netherlands: Montessori Pierson Publishing Company, 2019.