“Life’s most persistent and urgent question is: What are you doing for others?”

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Each year in January, students throughout the United States are given lessons about one of our nation’s most prominent civil rights advocates and leaders, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK). Along with lessons about the profound and impactful work he did during his life, students learn that he was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel at the age of 39 in Memphis, Tennessee.

Within days of Dr. King’s assassination, legislation was drafted by Rep. John Conyers to declare a federal holiday honoring his legacy. It would take some fifteen years, but in 1983, President Ronald Regan signed a bill declaring the third Monday in January as a federal holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. By 2000, all fifty states had declared it as a state government holiday.

Public schools, universities, libraries, and the United States Postal Service close on Martin Luther King Day, as do many private institutions (with exceptions for some public schools due to mandated minimum instructional days, loss of state funding for attendance, etc.). Whether or not schools close, many students learn about the work of Dr. King through stories, lessons, presentations, videos, etc. before or after the holiday.

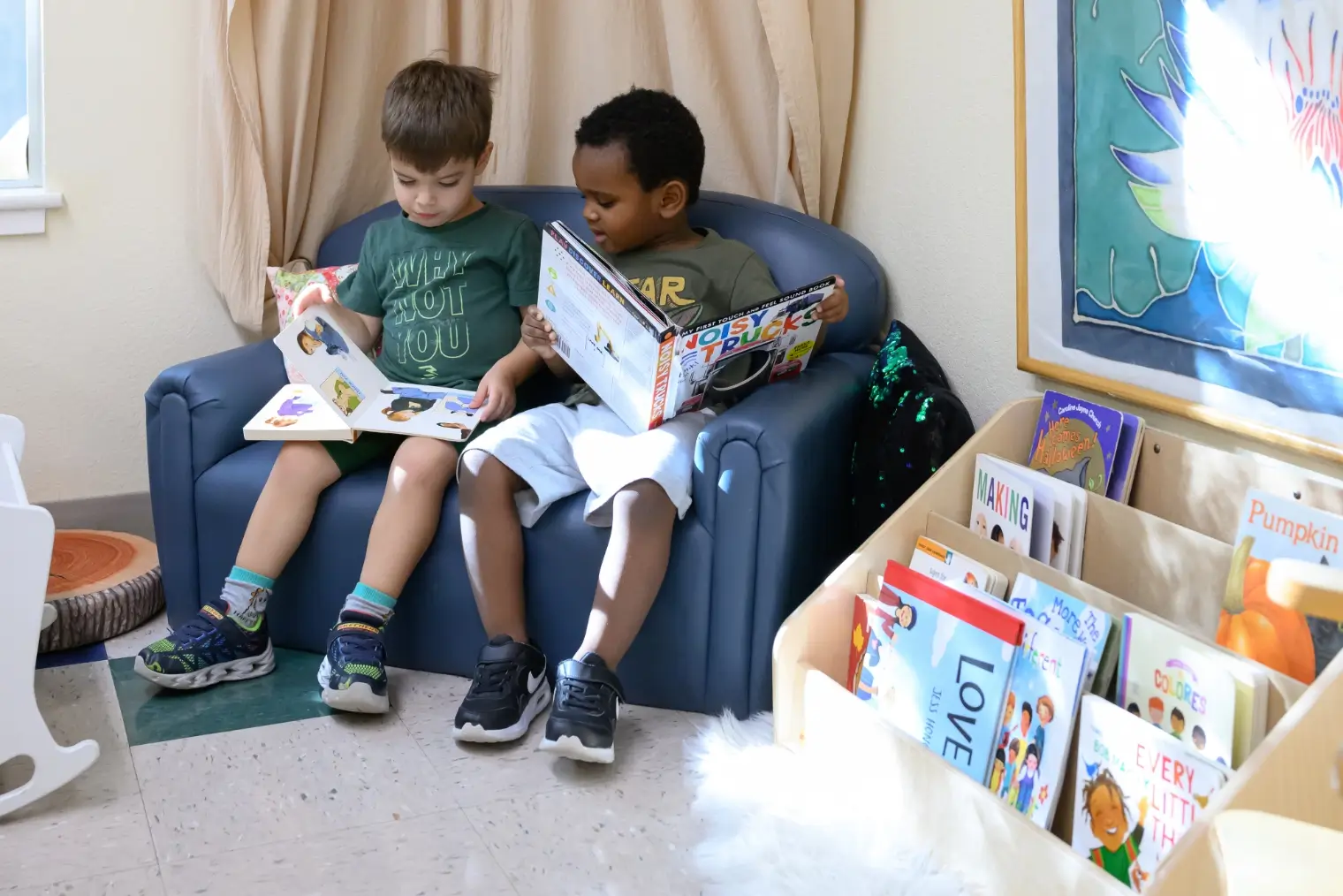

In this article, we take an interdisciplinary approach to offering ideas for teachers and parents to help elementary-age students learn about Dr. King’s important work and legacy. By exploring related concepts through various areas of the Montessori curriculum, they gain more relevance and meaning than would an isolated history lesson or story. We offer suggestions for work both in and out of the classroom.

History

The historical aspect of Dr. King’s work is, most obviously, centered around the Civil Rights Movement, some elements of which may be difficult for younger children to grasp. However, a range of age-appropriate stories are available that address the main themes of Dr. King’s life and work in terms both understandable and relatable by younger children—friendship, leadership, helping others, non-violence, peace, fairness, and standing up for what is right.

Older students may be able to grasp more difficult concepts by exploring the long view of the Civil Rights Movement, from its origins in the Reconstruction era following the Civil War, to its modern roots in the 1940s, and finally the social movement lasting from 1954 to 1968. This history is presented in accessible text in What is the Civil Rights Movement? Presented in manageable chapters, students can read about:

- A Troubled Past

- A Long Walk to School

- Montgomery Bus Boycott

- Lunch Counter Sit-ins

- Freedom Riders

- Children’s Crusade

- March on Washington

- Freedom Summer

- Selma to Montgomery

- Changing Times

One approach is to assign each chapter to a small group of students to read, take notes from, summarize, illustrate, and present to peers. Finally, each chapter summary, with accompanying artwork, could be integrated into a timeline, giving students a big picture view of the history and themes of the Civil Rights Movement.

Vocabulary and Writing

For children to truly grasp the impact of Dr. King’s work and the Civil Rights Movement, they need to understand the meaning of associated vocabulary. Any related resource students encounter through reading, research, listening, etc., will likely include terms like:

- boycott

- civil disobedience

- civil rights

- discrimination

- equal opportunity

- equity

- integration

- liberty

- non-violence

- passive resistance

- prejudice

- racial oppression

- racism

- segregation

- social justice

- unconstitutional

Adult guides could select from this list a group of words suitable for the child(ren) with whom they work, then:

- Words could be identified from different resources and discussed in context.

- Children could discuss these words with their families, having a conversation about the ideas they stand for, then create their own definitions rather than finding and recording dictionary definitions.

- Students could share and discuss different definitions with peers in class, then create vocabulary quizzes for each other based on their definitions.

- A selection of words could be made into a spelling list.

- Students could write a poem, story, booklet, paragraph, essay, report, etc., in which the words are used in context.

Grammar

Many children are likely to be familiar, to some degree, with Dr. King’s famous speech, “I Have a Dream.” After watching a video or listening to a recording, children could copy an excerpt and, using the grammar symbols, identify the parts of speech. The excerpt below, for example, contains the eight major parts of speech:

I have a dream my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character … I have a dream that little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today!

Oratory and Public Speaking

It has been suggested that Dr. King’s “greatest contribution to the Civil Rights Movement was his oratory,” or gift for public speaking. After listening to or watching a recording of one of Dr. King’s famous speeches, students could:

- discuss what makes an impactful public speaker, specifically, the effective use of phrasing, tenor, tone, cadence, pauses, etc.

- learn about other famous orators and the power of oratory in African American culture

- write their own “I Have a Dream” speech and practice their own oratory skills by reading their dream in a school presentation

Peace Education and Service

Peace education is integral to and links together different areas at every level of the Montessori curriculum, wherein materials and lessons are designed to de-emphasize nationalism, promote a global citizenship perspective, and foster not only the sense of the interdependence of all humanity, but also of each individual’s responsibility toward others. This notion is reflected in Dr. King’s vision, which “was not just about ending systemic racism and poverty but encouraging the formation of what he called a Beloved Community,” which:

. . . centers on the idea that people, regardless of race, nationality, or economic status, feel accountable to one another. The concept is not about being “in service” to each other based on shared backgrounds or similarities but based on our shared humanity.

Any classroom work centered on Dr. King’s work—especially his legacy of non-violence and service—is, by definition, peace education. (Parents and teachers might also be interested in these additional activities for teaching and practicing peace with children.)

Work outside the classroom, however, is as important, if not more so. While technically a holiday, Martin Luther King, Jr. Day is widely regarded as a day on, not a day off. In 1994, President Clinton signed the Martin Luther King Federal Holiday and Service Act, “the first-ever federal holiday observed as a National Day of Service,” expanding the original mission to include service to one’s community. In Dr. King’s words:

Everybody can be great because everybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve. You don’t have to make your subject and your verb agree to serve. You only need a heart full of grace, a soul generated by love.

Helping students find ways to participate in service by giving back to the community brings a deeper level of meaning to the holiday and recognition that one person’s service can make a difference. Through work both inside and outside the classroom, parents and teachers can help children learn about the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in ways that build knowledge and strengthen academic skills, and more importantly, honor the legacy of one of history’s most revered civil rights leaders through service to others. The work continues.