“The mere imparting of information is not education.”

– Carter G. Woodson

African-American contributions are “overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them,” according to Carter G. Woodson. He would go on to address this issue with the creation of the Journal of Negro History (still published today under the name Journal of African American History) and Negro History Week, which would later become Black History Month.

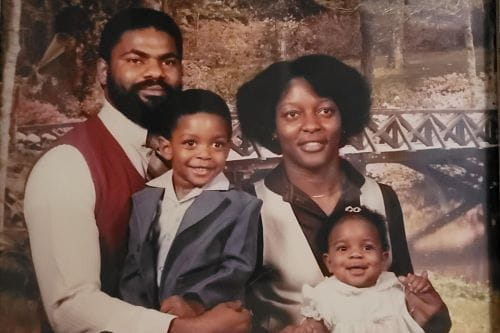

I grew up in a household that understood Mr. Woodson’s sentiment and response on an exoteric level. My father and mother graduated high school in 1971 and 1976 respectively, and were both raised in the segregated Jim Crow south but became young adults in the newly integrated world that had yet to see them as whole humans. Therefore, when my brother was born in 1980 and me two short years later, my parents were immensely dedicated to raising us as they were raised, in a predominantly Black existence.

“Children learn more from what you are than what you teach.” – W. E. B. Du Bois

Reading books with pictures of princesses, kings, race car drivers, teachers, and more who looked like the members of my family were a dime a dozen in my home. Even in the cramped apartment, multiple bookshelves with novels and poems by and about Black people lined the shelves and were my go-to reading material on rainy or cold days when I couldn’t go outside to play with my siblings and friends. I now understand that my parents were clear on the messaging that they intended to send. They knew what we might face outside of our home and they wanted to be sure that we would remain confident in who we are.

My parents enrolled us in magnet schools and always sent us to “the good schools” so that we could get the best education possible, but I never understood why they were so adamant about us learning and reciting things like the Black National Anthem or other encouraging poems and proverbs before leaving each day. When we returned home, my parents were always interested in how our day went, but even more so with questions like: how we were treated at school and did people pronounce our names correctly. As an adult and parent, I now understand that the energy behind those questions was fear and anxiety.

“The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worthwhile, depresses.” – Carter G. Woodson

I went through school enthusiastic about learning and have always experienced academic success as a student. However, I always found myself having talks with the teacher or other administrators about my “attitude.” “I don’t have an attitude,” I would persist, “I just don’t know how I ended up in an AP U.S. History class where we have made it all the way to Industrialism and haven’t found a single Black person yet! I can bring books from home if you need more materials.” **insert teenage eyeroll here** As an adult and parent of an enthusiastic learner, I now understand that my “attitude” was actually frustration and resentment from not only being excluded, but being inadequately educated.

The thought of being amongst people who would undoubtedly share my culture and experiences brought me so much joy and, upon graduation, I made the decision to attend an HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) for my college education. Back when landline phones were still a thing, people would call and ask for my roommate. I quickly got used to her saying these three words: “No. She’s Black.” They were asking about me?! She finally clued me in that my proper use of the English language led everyone to believe that I was white.

While I understood, I was admittedly taken aback. We were in college. Aren’t all college students supposed to demonstrate their intelligence with a masterful use of the English language? As an adult and a parent who has learned that intelligence comes in the many ways that we use language and express ourselves, I now understand that my masterful use of the English language at all times was a learned behavior that “proved” to others that I was intelligent and therefore worthy of belonging.

Journeying into adulthood, I have encountered countless other lessons that have taught me something that I now understand.

My home is no longer a cramped apartment, but my many bookshelves still line the walls with books by and for Black people. I now understand that it is essential for people to see themselves in the world at all times and in all ways.

While I understand the anxiety and fear that my parents must have had in sending us to integrated schools, my afterschool questions have changed a bit. I now understand that being proud of who you are and advocating for your humanity are essential to a person’s security.

Curriculum has changed very little since I was in high school and so has my dissent with the material. However, I now understand the importance of providing children with a true, deep understanding of the facts of our history as a people.

“Philosophers have long conceded, however, that every man has two educators: ‘that which is given to him, and the other that which he gives himself. Of the two kinds the latter is by far the more desirable. Indeed all that is most worthy in man he must work out and conquer for himself. It is that which constitutes our real and best nourishment. What we are merely taught seldom nourishes the mind like that which we teach ourselves.” – Carter G. Woodson

Even with an upbringing steeped in Black history and self-awareness, I found myself as a young adult dealing with and unpacking my own anti-Blackness. I now understand that everyone was indoctrinated in the same systems that were initially designed for wealthy, white men and that everyone will have to “do the work” to be mindful of their decisions made through this perspective.

This understanding helps set the stage for the way that I approach my work in school accreditation and throughout the AMS community. An understanding that all people and places have a culture with aspects that overlap with others. Cultures derive from a place of perception, tradition, necessity and purpose to name a few. As communities grow and refine who they are, those cultures do as well and school accreditation work allows me to help schools identify what their culture is, how it pushes their mission forward, and what perspectives or added considerations might be beneficial in helping them reach their Montessori goals.

And through all of this reflection, I now understand what it means to stand on the shoulders of my ancestors. Through the foundation set by my parents, I am able to go further and expect more, but only by acknowledging who I am, where I come from, what is important to me in service to my mission, and what other perspectives might be needed in order for me to continue learning and growing. The challenges that were encountered and overcome to allow me to be positioned as I am, are lessons that I can learn without enduring the hardships, but the legacy I get to pass down to my children which will continue to propel them forward for generations to come.