What comes to mind when we think about the Montessori biology curriculum? How do we articulate our curriculum on school websites, in parent education meetings, and even in Montessori teacher education programs (TEPs)? For some of us, we go straight to plants and animals. We may highlight the extensive nomenclature material for the parts of vertebrates, invertebrates, leaves, flowers, and seeds, or the traditional first knowledge work, or how plants and animals meet their needs. Some might include fungi, fewer still the protists and prokaryotes. How many others think of phylogenetic trees and evolutionary history? Adaptations? Do we talk about the lineages of life and shared ancestry?

The field of biology has changed, and continues to change as technology advances and new discoveries are made. These changes need to be reflected in TEPs and classroom biology curriculum if we wish to provide first-rate Montessori education. This is the first in a series of articles examining both biology updates and other aspects of biology—of science, in general—that need to be reviewed and considered in many TEPs and Elementary classrooms.

One of the most dynamic aspects of biology is the way in which living things are classified or otherwise grouped, and this work is a central topic of the life science curriculum. As such, Part One of this series addresses classification updates in the field of biology.

A Classification Timeline

Before teachers can truly appreciate the current system for grouping living things, familiarity with the history of classification may be helpful. To this end, a summarized timeline follows:

- 1735 – Carl Linnaeus establishes two kingdoms: Vegetabilia (plants); Animalia (similar to that of Aristotle, 2000 years earlier)

- 1866 – Ernst Haeckel proposes a kingdom for protists and establishes a three-kingdom approach: Protista; Plantae; Animalia

- 1937 – Édouard Chatton characterizes the distinction between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells and coins these terms, thus establishing the two-empire system—Prokaryota and Eukaryota as the top level of classification

- 1938 – Herbert Copeland proposes establishing the prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea, formerly classified together as a phylum of protists) as Kingdom Monera, thus adding a fourth kingdom to the two-empire system

- 1969 – Robert Whittaker proposes a separate kingdom for fungi, given their distinct differences from plants, and the five-kingdom approach is established: Monera; Protista; Plantae; Fungi; Animalia (readers can access the full story of Whittaker’s work, and its consequences, here).

- 1977 – Carl Woese proposes a six-kingdom approach within the two-empire system, by subdividing Monera into two kingdoms: Kingdom Eubacteria and Kingdom Archaebacteria

- 1990 – Carl Woese proposes a revision to the two-empire, six-kingdom approach to a three domain approach, with the term domain being accepted as the highest rank: Domain Bacteria, Domain Archaea, Domain Eukarya.

From 1990 to 2015, several other combinations of kingdoms, super-kingdoms, and empires were proposed. Today, the system most widely accepted by biologists is the three-domain approach proposed in 1990 (the number of kingdoms is an open question, and will be addressed in Part Two of this series).

Relevance to Montessori Education

Looking closer at the timeline above, we see that while there were two shifts in approaches to classification during Montessori’s lifetime (1937 and 1938), taxonomic models had been relatively stable for a long time. Moreover, given the usual gap between research and education, these changes were not reflected in textbooks until the 1960s, nor were they incorporated into the lessons and materials that Montessori created—lessons that later became the biology content for teacher education programs. Added to this, biology began to undergo a revolution right around the time of Montessori’s death. New discoveries in the field of biochemistry and the discovery of the structure of DNA opened up a new world of biology (Spears 2021).

E. O. Wilson, the preeminent American biologist and naturalist, wrote about this revolution, noting “that during the 1960s, ‘biology spun through a ninety-degree turn in its approaches to life’ as many biologists turned away from studying whole organisms and biodiversity in order to focus on cells and molecules” (Hagen 2012). One supposes that Montessori would have updated the curriculum in light of these revolutionary discoveries, beginning with relegating to the history of science those traditional Montessori charts of rows and boxes reflecting Linnaean ranks.

Why does any of this matter, and why is it important for Montessori teachers and trainers to know? The primary reason is that we are preparing the scientists of the future; presenting anything less than the most current science knowledge is a disservice to our students. Furthermore, teachers and students need to recognize the dynamic nature of the inquiry process in the field of biology. A more thorough reading of the reasons behind the major changes outlined above reveals new discoveries at the molecular and biochemical levels brought about by advanced technologies. New information requires new models and approaches; this is the very nature of science, something about which children also need to learn. “Biology is much more than classification and learning the names of the parts. In every lesson, it is important to note how we know what we know and that we are still learning” (Spears 2021). In other words, it is important to share current thinking in science, and science news in general, with children. (Science News is a very good resource for non-scientists and also includes a student version.)

Life Science Lessons in Montessori Classrooms Today

The Montessori community took notice of the introduction of the five-kingdoms model in the mid-to-late 1990s. A few materials companies produced posters, charts, and cards reflecting the new system for classifying life, and Five Kingdoms (1982), by Lynn Margulis and Karlene Schwartz, became recommended reading in some Elementary TEPs. These ideas were gradually incorporated into the curriculum of the life science component of many TEPs and Montessori Elementary classrooms, where, in many programs, they remain today. An informal search of “Montessori school Elementary biology curriculum” by the author yielded a predominance of hits for the five-kingdom approach to teaching life science, and the materials to support this are nearly ubiquitous on Montessori materials websites. But given that the five-kingdom approach has been obsolete for at least twenty years, this is problematic. Teachers, however, should not be solely responsible for updating curriculum.

Classroom teachers are responsible for presenting lessons in life science, yes, but also physical science; history and geography; math and geometry; and a range of areas in language arts. And since Montessori education does not take a one-size-fits-all approach, teachers are not only planning lessons in a range of curriculum areas, but they are individualizing lessons within those areas as well—a tremendous responsibility that takes no small measure of time. Few teachers have the time to think about biology updates, much less research and learn these on their own. Moreover, it is not a simple matter of revising a few lessons, but rather one of restructuring a good portion of the biology curriculum, with no procedure in place for doing so. And yet, while anyone with classroom experience can appreciate this perspective, the fact remains that outdated approaches for teaching about the classification of life are widespread in Montessori classrooms today despite their obsolete status with biologists. Teachers need support in correcting this.

What’s Wrong with the Five-Kingdoms?

There is nothing inherently wrong with the five-kingdom approach to classification; it is a functional way of dividing life into sections for study, but like all Linnaean classification, it is a snapshot of extant life that omits the history of life and relationships between the categories. At one time, however, it was the best model—and the most universally accepted among biologists—for classifying life on Earth. The five-kingdom approach, in fact, was very much in line with educational reforms that shifted the emphasis in biology instruction from “detailed taxonomic and anatomical surveys” to “greater attention to cell biology, genetics, development, animal behavior, and ecology” (Hagen 2012). Hagen points out that the five-kingdoms offered “a more compelling way to describe the broad classification of organisms than the traditional plant–animal dichotomy.” But even while the five-kingdom approach was gaining prominence, technology marched forward—specifically, the ability for biologists to study genetics at the molecular level—and Whittaker’s approach was gradually replaced by the system most commonly accepted by biologists today: phylogenetics.

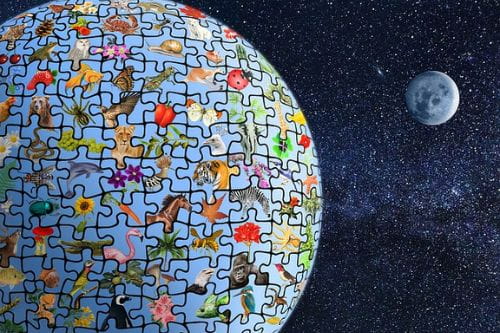

Phylogenetics (literally “origin of the tribes”) refers to the grouping of organisms based on common ancestry, or evolutionary history; that is, it connects extant organisms to their recent and distant ancestors. “Biologists use DNA data along with morphology (the physical characteristics of the organism), developmental patterns, and other information to determine how living things are related … The more recent the common ancestor, the more closely organisms are related” (Spears 2021). These relationships can be seen through a phylogenetic tree or phylogeny, more commonly known as the Tree of Life. And while Elementary-age children will not study the molecular genetics and biochemistry underlying these relationships, they can and should learn to read phylogenetic diagrams that show lineages of life and how they are related.

Where Do We Go from Here?

As teachers, it is easy to become habituated with the tried-and-true Montessori lessons, without questioning content, but it is important to recognize that when we teach children about classification using outdated models, we put them in the position of having to unlearn information when they encounter updated biology concepts in newer high school and college textbooks. We would be remiss, as teachers and teacher trainers—as Montessorians—not to provide the most up-to-date biology content in our life science lessons, not to give students a strong foundation in concepts they are sure to come across in their future studies. In Part Two of this series, we will:

- Explore the three-domain system in greater detail

- Introduce phylogenetic trees

- Introduce relevant vocabulary

- Direct the reader to some teacher resources for understanding phylogenies and the Tree of Life

In the meantime, readers are encouraged to consult Kingdoms of Life Connected: A Teacher’s Guide to the Tree of Life, by Priscilla Spears. And don’t throw out those old Montessori charts of rows and boxes or your five- or six-kingdom charts; they are still useful and important for history of classification lessons.

Other References (not linked)

Spears, Priscilla. “Life Science Literacy,” Unpublished manuscript, November 1, 2021, typescript.

About the Author

The opinions expressed in Montessori Life are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of AMS. On this page |