About Montessori

Montessori is a holistic, experiential, child-directed system of education, developed by revolutionary educator Dr. Maria Montessori over a century ago. This scientifically-validated approach is now practiced worldwide.

“The child who has never learned to work by himself, to set goals for his own acts, or to be the master of his own force of will is recognizable in the adult who lets others guide his will and feels a constant need for approval of others.”

— Maria Montessori, Education and Peace

Benefits of Montessori Education

- Montessori Education focuses on the whole child, fostering rigorous, self-motivated growth in all areas of development—cognitive, emotional, social, and physical.

- Children develop a strong sense of curiosity within a nourishing environment.

- Concentration, confidence and independence are nurtured from an early age.

- Students are part of a close, caring community.

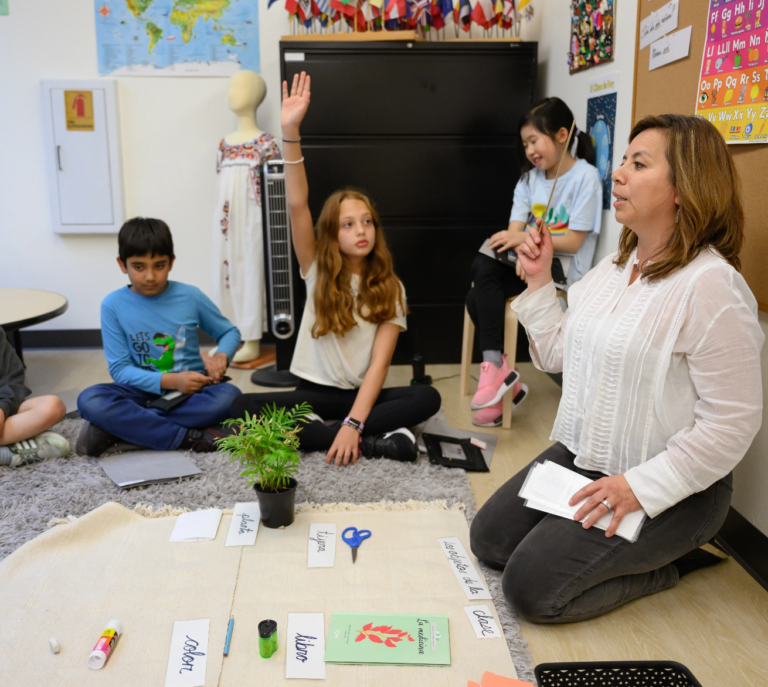

Inside the Montessori Classroom

See how a typical classroom balances structure with exploration so every child has room to discover their talents.

Notable Montessori Alumni

Living proof that guiding your child towards self-learning can lead to unprecedented success.

Backed by Research

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the success of Montessori’s holistic approach in achieving strong student outcomes – academically and beyond.

Montessori FAQs

Do Montessori schools assign homework?

It is unusual for the youngest students to receive homework. Generally, parents can expect that as students mature through the grade levels they will be given homework. When this happens, students are expected to spend approximately 20 – 40 minutes completing the task on their own. Young children (ages 6 – 8) may be asked to read to their parents, or complete a project that is started at school. As students move through the Montessori program, more responsibility for completing homework is expected.

Do Montessori schools follow a curriculum?

Montessori schools teach the same basic skills as traditional schools, and offer a rigorous academic program. Most of the subject areas are familiar—such as math, science, history, geography, and language—but they are presented through an integrated approach that weaves separate strands of the curriculum together.

While studying a map of Africa, for example, students may explore the art, history, and inventions of several African nations. This may lead them to examine ancient Egypt, including hieroglyphs and their place in the history of writing. And the study of the pyramids is a natural bridge to geometry!

This approach to curriculum demonstrates the interrelatedness of all things. It also allows students to become thoroughly immersed in a topic—and to give their curiosity full rein.

Do Montessori schools have grades?

Montessori students typically do not receive letter or number grades for their work. Grades, like other external rewards, have little lasting effect on a child’s efforts or achievements. The Montessori approach nurtures the motivation that comes from within, kindling the child’s natural desire to learn.

A self-motivated learner also learns to be self-sufficient, without needing reinforcement from outside. In the classroom, of course, the teacher is always available to provide students with guidance and support.

Although most Montessori teachers don’t assign grades, they closely and continuously observe and assess each student’s progress and readiness to advance to new lessons. Most schools hold family conferences a few times a year so parents may see samples of their child’s work and hear the teacher’s assessment—and perhaps even their child’s self-assessment.

How is Montessori education “scientifically-validated”?

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the success of Montessori’s holistic approach in achieving strong results on both academic and non-academic student outcomes. Find the specific research citations here.

Is Montessori appropriate for children with disabilities and neurodivergences?

The Montessori Method of education provides a nurturing, supportive environment for children of all abilities and learning styles. This includes children with disabilities and neurodivergences, including physical disabilities; learning differences in reading, writing, spelling and/or math; ADHD; and autism spectrum disorders.

Children learn in multi-age classes, with the same teacher, for 3 years. This sustained connection creates a stable, predictable environment for adults and children alike. Students are able to attend to their learning, rather than having to adjust to new people and new routines every year. For more information on Montessori and children with disabilities and neurodivergences, please visit this page.

What ages do Montessori schools serve?

Currently, most Montessori programs begin at the Early Childhood level (for children ages 2.5 – 6 years). However there are also programs for infants and toddlers (birth – age 3), Elementary-aged children (ages 6 – 12), and Secondary students (ages 12 – 18). Some schools refer to the first part of the Secondary level as Middle School (ages 12 – 15) and the second part as High School (ages 15 – 18).

What are the benefits of a Montessori education?

Montessori education is own for individually paced learning and fostering independence, the Montessori Method also encourages empathy, a passion for social justice, and a joy in lifelong learning.

Given the freedom and support to question, to probe deeply, and to make connections, Montessori students become confident, enthusiastic, self-directed learners. They are able to think critically, work collaboratively, and act boldly—a skill set for the 21st century.

For details on how a Montessori education provides these benefits, check out this page.

What are the benefits of multi-age Montessori classrooms?

The multi-age classroom is designed to create natural opportunities for independence, citizenship, and accountability—children embrace multi-sensory learning and passionate inquiry.

Multi-age groupings enable younger children to learn from older children and experience new challenges through observation. Older children reinforce their own learning by teaching concepts they have already mastered, while developing leadership skills and serving as role models. Learn more about the multi-age classroom component on our 5 Core Components of Montessori Education page.

What does transition from Montessori to traditional school look like?

A growing body of research comparing Montessori students to those in traditional schools suggests that in academic subjects, Montessori students perform as well as or better—academically and socially—than their non-Montessori peers. These benefits grow as children have more experience in a Montessori environment.

Most Montessori schools report that their students are typically accepted into the high schools and colleges of their choice. And many successful graduates cite their years at Montessori when reflecting on the important influences in their life.

What enrichment opportunities are offered for gifted Montessori students?

An advantage of the Montessori approach—including multi-age classrooms with students of varying abilities and interests—is that it allows each child to work at his or her own pace. Students whose strengths and interests propel them to higher levels of learning can find intellectual challenge without being separated from their peers. The same is true for students who may need extra guidance and support, including students with special needs such as ADHD, learning differences, and autism spectrum disorders: each can progress through the curriculum at her own comfortable pace, without feeling pressure to “catch up.”

From a Montessori perspective, every child is considered gifted, each in his own way. Every child has unique strengths and interests that the Montessori environment nurtures and supports.

What is the role of a Montessori teacher if the work is child-led?

When you observe a Montessori teacher at work you may be surprised! You will not see them standing in front of the classroom teaching the same lesson to the entire class, because the Montessori curriculum is individualized to the needs, interests, and learning style of each child. Often you will find the teacher on the floor, working with an individual child. With the older children, the teacher may be giving a small group lesson, or demonstrating a lesson or activity that the students will then complete on their own.

One of the many roles of the Montessori teacher is to observe each child and the classroom community as a whole and make adaptations to the environment and lesson-planning as needed to support each child’s development. As the Montessori teacher observes, they are determining when and how to introduce a new challenging lesson to a student, and when to review a previous lesson if a skill has not yet been mastered.

While a Montessori student may choose their activities on any given day, their decisions are limited by the materials and activities in each area of the curriculum that the teacher has prepared and presented to her. The teacher’s observations inform each child’s personalized learning plan and allow each child to move through the curriculum at an appropriate pace and level of challenge.

What materials and lessons are unique to Montessori?

A hallmark of Montessori education is the hands-on approach to learning and the use of specially designed learning materials. Beautifully and precisely crafted, Montessori’s distinctive learning materials each teach a single skill or concept such as math materials, language materials, and sensorial materials. The materials follow a logical, developmentally appropriate progression that allows the child to develop an abstract understanding of a concept.

To learn more about classrooms, visit our Inside the Montessori Classroom page.

What sort of parental involvement do Montessori schools expect?

Montessori expects parent education, classroom observation, and providing enriching learning experiences. Learn more about Montessori at home here, or sign up for our course You and Your Child’s Montessori Education: Early Childhood on our online learning platform, AMS Learning.

What will my Montessori child do if there isn’t a higher-level program for them to transition into?

As your child transitions out of a Montessori environment to another type of program, they are likely to thrive socially and academically. Poised, self-reliant, and used to working harmoniously as part of a classroom community, students who move from Montessori typically adjust quickly to the ways of their new school. Learn more about continuing your child’s Montessori education here.

Why look for AMS affiliation?

AMS affiliated programs—from schools to teacher education—are dedicated to meeting quality standards, and work to provide an authentic Montessori Education.

From the Montessori Life Blog

Montessori Life Blog is the go-to resource for anyone interested in staying up to date on the latest news and trending topics in the world of Montessori.