Montessori Life, Summer 2017

by Geoffrey Bishop and Mirko Sever

A BABY BOOMER VOICE: GEOFFREY BISHOP

I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in Australia, a country that was itself coming out of the closet, although the closet was heavily fortified and for a long time quite impenetrable when it came to its acceptance of gay people. Growing up gay is very different from growing up straight; your sexuality defines you in a larger way. The sexuality of straight children is not dwelt upon to the same degree, because straight is “normal.” It is what you see every day: your parents, people on TV, your teachers, and the majority of the people around you. On the other hand, growing up gay starts with a small seed, a feeling that you do not understand, and an attraction to the same sex you at first think is normal. Soon, however, you discover the meaning and the reality of this attraction—that being gay is something you should be ashamed of, and, from a religious perspective, something seen as evil. And from the moment of that discovery, this awareness and what you are hiding start to define, and even take over, your whole being.

I knew I was gay from a very young age, probably 7 or 8, or even earlier, though I didn’t know the word gay. At that time, the word poofta (or poofter) was a commonly used Australian term for a gay male. I understood that in some ways this term meant me. I was also very aware that, for many people, being gay was akin to being a prostitute or being immoral. It was also very clear to me that being gay only meant sex; it had nothing to do with love, as I had no gay role models and I had never met a gay person.

At age 11, I left home to attend an all-boys boarding school. This saved me but also drove me deeper into the darkness of the closet. It saved me because it opened a whole world that I did not know about, exposing me to students from all over the South Pacific, along with cultures and ideas that were not available during my life on a sheep station. It also opened a door to a darker side; I was so terrified of being outed that I sometimes acted as the loudest bully toward others suspected of being gay. Every day I wore a mask to hide who I really was. This inner battle became a daily struggle: Deep down, I knew that everything about the way in which I presented my identity was a lie. When I had crushes on other boys, I had to keep them hidden, unfulfilled, when all around me, peers were getting so excited about romance and love. All I could do is dream that one day I would have friends who would be happy when I had my first boyfriend.

My experience was a long time ago, and though much has changed in the world, not much is different for many young people who are trying to define who they are. Many adults presume that every child is straight; for many parents, the thought that one day their child will turn to them and say, “Mom, Dad, I’m gay” is terrifying. This may be the hardest sentence a young person will ever have to utter, and, for many, it has terrifying consequences. Some gay children are lucky enough to have parents who love and support them as they come out of the closet, but, for others, it is a huge gamble, as the thoughts that echo in their mind are, What will their reaction be? Will they still love me? I wish I were normal.

It is 2017, and I still have friends who are not out at work or to family members. Even at my age, this is a treacherous road for them. To have a voice, you need to be supported, and you need to have confidence that that voice will not destroy you. This takes an enormous amount of courage that many LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) individuals are unable to summon.

A MILLENNIAL VOICE: MIRKO SEVER

Growing up, I knew I was different, but I could not explain why. Most of my male peers were interested in soccer, Power Rangers, and girls. I was not. At a young age, I realized I was attracted to other boys, but acting on that did not come till adulthood. Growing up in a religious family, I was surrounded by images, comments, and information that contradicted what I felt inside. This was confusing and also made me feel that expressing what was inside me was a great risk. I could not relate to other boys, and, because of that, I was left out and made fun of. I felt invisible. I had no friends, so I turned to my teachers and other adults, hoping they would understand and accept me. Unfortunately, I also found them intolerant, unsupportive, and unable to see the real me. I got used to being alone.

Without anyone to confide in, my self-image took a huge beating. I constantly put myself down. I believed that since others did not see the value in me, I must not have any value to provide. Very dark thoughts entered my mind. I began to treat myself the way others treated me: with disrespect, discouragement, indifference, and carelessness. Nobody cared how I felt, no one cared how I was doing, no one cared that I needed help, and no one remembered my birthday. Feeling great anxiety about whether I was living in sin ate at me daily. I longed for nights where I didn’t have to cry myself to sleep. I longed for love without the condition of being gay.

But deep down, I knew I was here for a reason, even if I could not figure it out. I knew I had to pull myself out of the feeling of uselessness that had come over me. I began to spend all my time studying or working, in an attempt to keep my mind from focusing on the sad reality of my life. I knew that there would be light at the end of the tunnel. I believed God had a greater plan for me and that I was on Earth to make the world a better place. But I still didn’t know why I was created this way or what I could do about it.

As I pondered these thoughts, I came to understand that the world was filled with hatred—the same hatred that had been directed toward me and the same self-loathing I had developed as a result. What I had experienced was horrible; I made it my mission to ensure that no other child would have to go through it. I believe I was put through so much pain because I was strong enough to overcome it and help others overcome. Instead of remaining bitter, I chose to adopt a lifestyle of kindness.

In many of the world’s countries, being gay is punishable by death (Bearak and Cameron, June 16, 2016). And in the United States, there has been recent political opposition to gay marriage and gay rights. It is no wonder that, in today’s world, a small but important percentage of our young people grow up confused, scared, and unsupported. A CDC study found that 43% of LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) students in grades 9–12 had seriously considered suicide. Questioning youth attempt suicide at a rate two times greater than that of straight youth; for LGB youth, the rate is four times that of straight youth (thetrevorproject.org). In this article, we offer two perspectives on how growing up gay affected our lives and propose our thoughts on how schools and teachers can try to normalize what society often overlooks, misunderstands, ignores, or even considers to be outside the realm of reality.

I also realized that being gay is how I was born, not something I chose. I began to understand that I needed to accept myself. I needed to make myself happy.

I needed to love myself. I needed to set myself free. Once I came out to myself, I was able to do those things, and life became easier and more enjoyable. I began to love who I was and who I could be. And when I gained the courage to come out to others, I found that, for most of my friends, it made no difference. True friends love you for who you are and accept all the things that make you you.

I realized I had been trying to fit into the mold that society had created for me—the middle-class white man who excelled in school and career, and eventually met, married, and started a family with the woman of his dreams. But this wasn’t what I wanted. Attempting to conform to these standards caused me to think twice about every decision I made, every word I said, and every truth I accepted or conveyed. I came to understand that my journey wasn’t about becoming anything but rather about un-becoming everything that wasn’t really me so I could be who I was meant to be. When I began to understand myself and understand why I was to make the world a better place, I realized that I didn’t have to fit society’s mold; I could create my own. I could take the shell that surrounded me, squeezed me, and kept my wings from spreading, and I could shatter it.

Though this realization was a relief, it brought me to an extremely difficult decision: I could either continue living a lie and living in fear, or I could come out of the closet. Taking everything that provided me “comfort” for so long and destroying it provoked as much anxiety as living the lie. In the end, I decided that coming to terms with being gay was more important and more conducive to removing hatred from the world and making it a better place to live. Immediately I was able to breathe more easily. I didn’t have to think twice about what I said anymore; I could live in real truth. As a result, I created new friendships with people who loved and accepted me for who I was. These new friends cared about me. They cared enough to ask if I needed help; they cared enough to get together and celebrate my birthday. I could finally be free and feel loved. I could finally go to bed happy. All of the things I had once prayed for I was now living.

I believe that every adult in charge of children should keep these mantras in mind:

- In everything I do, I will strive to include everyone;

- I will strive to listen to those who have no one to listen to them;

- I will strive to encourage others and support their dreams and desires;

- I will strive to uplift others.

For much of my life, I knew what it was like to feel left out, ignored, and unsupported, and so I told myself if no one could be or do those things for me, I could at least do them for someone else.

What can Montessori schools do to aid LGBTQ students? The first and most important thing an adult can do is not to presume anything about a student. It is so easy for us as teachers to create an image in our heads of who we believe a child to be. But we must remember that the child is the only person who truly knows who he or she is inside, and many LGBTQ children are still working that out for themselves. Montessorians already strive to create environments designed to foster self-direction and independence. Let us also work to ensure that these environments are safe and comfortable places for children who are coming to grips with their own identities.

The media and politicians often reduce gay people to the act of sex with someone of the same gender. Sex is only one small part of who humans are, and at our schools we must broadcast that this goes for LGBTQ students and adults as well as for straight students and adults. Being gay is about loving someone of the same gender. Beyond that, gay people’s dreams, goals, and aspirations often are not distinguishable from those of straight people.

As educators, we should never assume that the parents of a gay or lesbian student who has confided in us are as open or understanding as we are. It is not our role to “out” children to their parents or to anyone else, including our peers. No one has the right to declare another’s sexuality.

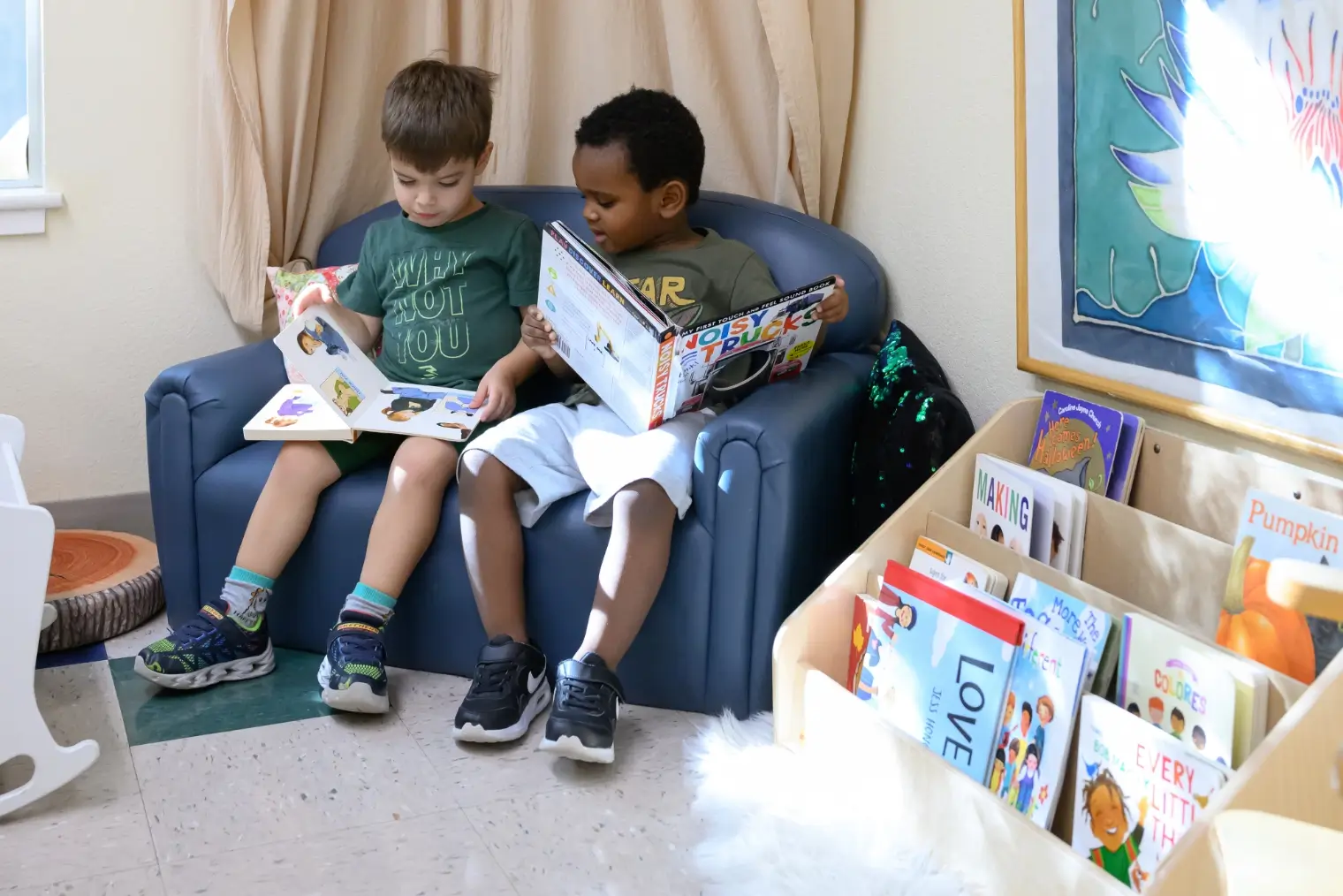

We can use books and other materials to present and normalize various kinds of relationships and families. Exposure to positive and open representations of all types of families will plant seeds in even the youngest children that can support healthy relationships with their own sexuality, whatever it may be.

We should be proactive about sex education, creating programs that are reflective of and positive about LBGTQ relationships and straight relationships alike. The best sex education programs should always include parents; creating an avenue for open dialogue between parents and students can lead to healthy, mature, and well-adjusted young adults. As Montessori said, the parent is the first educator.

The statistics on LGBTQ suicides across the country are astounding, and it is such a waste of human potential. All of us have great talents and so much to give to society. Who we love is a beautiful thing and should be celebrated, not driven into the dark, creating an endless cycle of self-hatred. We all have a role to play in raising and educating children. One positive word from a teacher, one story of inclusion, or a few minutes empathically listening can save the life of an LGBTQ child. As teachers and Montessori professionals, we want to discover the inner child in our students, to see who they are as humans; along with everything else, this includes their sexuality. We are all created as individuals, with various needs, desires, and aspirations. It is through a caring community, accepting adults, and the encouragement of our peers that we are able to release our true potential. It’s up to all of us.

About the Author

GEOFFREY BISHOP is the founder of Nature’s Classroom Institute and Montessori School, a 140-acre campus in Mukwonago, WI. Contact him at geoffrey@nciw.org.

MIRKO SEVER is the marketing and program director for Nature’s Classroom Institute, California. Contact him at mirko@discovernci.org.

References

Bearak, M. & Cameron, D. (2016, June 16). Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punishable by death. Washington Post. Retrieved from www.washingtonpost.com .

The Trevor Project. Retrieved from www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/entry/cdc-study-reveals-lgb-youth-three-times-more-likely-to-experience-sexual-ph