Montessori Life, Summer 2017

by Charles Goehring and Hillary Whittington

Essay Terms

- Transgender – An umbrella term to describe individuals whose sense of gender identity and expression does not correspond with their biological sex assigned at birth.

- Gender Nonconforming – A concept whereby individuals exist and act outside of traditional gender norms.

- Cisgender – A term used to denote individuals whose gender identity conforms to the designated biological sex (e.g., A cisgender male would identify as male and be born with male genitalia.)

- Gender Affirmative – A model developed by Ehrensaft et al. to denote acceptance of a child’s gender identity.

- Gender Constancy – An individual’s understanding that the assigned gender is constant and is accompanied by expectations related to that gender; this occurs as early as 3 years old but no later than 6 years old (Rivers & Barnett, 2011).

- Gender inclusivity – The idea that all gender identities and expressions should be validated and included.

- Gender Variance – An individual’s behavior or gender expression that fails to align with expected or traditional gender norms; see also gender nonconforming.

- Gender Diversity – The notion that issues of diversity should include gender in all its variations. While it is often understood as equal representation, acceptance, and fairness for both men and women, increasingly it has expanded to incorporate gender variation outside of a binary.

On its website (amshq.org), the American Montessori Society lists six values that guide its work. In this essay, we touch upon at least three of those values (inclusiveness, diversity, and respect) as we offer suggestions on incorporating gender diversity into an already existing framework of inclusivity, in order to create a safe and affirming space for children. We understand gender diversity as the notion that issues of diversity should include gender in all its variations, and gender inclusivity as the idea that all gender identities and expressions should be validated and included. We are a communication scholar who studies gender identity and rhetoric (Charles) and an activist for transgender people and parent of a transgender child (Hillary). Given our backgrounds and experience, we hope to provide best practices and resources to help Montessorians navigate the sometimes confusing road to gender inclusivity. We follow the path put forth by AMS executive director Richard Ungerer, who wrote, in 2013, about preparing Montessori teachers (and administrators) for a more diverse world and for “celebrating diversity and differences as positives rather than challenges to overcome” (p. 3).

The purpose of this essay is not simply to help those students who may be experiencing a transgender identity but also to help educators and all students begin the process of communicating and interacting in ways that will make other students comfortable with their own identities and with alternative understandings of gender. In what follows, we first discuss the concept of allowing children to be their authentic selves. Next, we offer some communicative tools to foster a sense of inclusivity and affirmation. Then we consider policy concerns, especially regarding bathroom use and gender-based bullying. And, finally, we suggest schools revisit the language of their policies.

The term transgender is an umbrella term to describe individuals whose sense of gender identity and expression does not correspond with their biological sex assigned at birth. Being transgender is like any other human variance or genetic difference (skin color, eye color, color blindness, etc.), yet this difference has unimaginable repercussions and is accompanied by alarming statistics. Based largely on common misunderstandings and deeply rooted religious beliefs, gender-nonconforming people have been targeted, discriminated against, and victimized around the world for decades. A 2012 study found that 41% of transgender individuals have attempted suicide due to lack of societal acceptance, a staggering number when compared to a 1.6% attempted suicide rate in the general population (Grant, Mottet, Tanis, Harrison, Herman & Keisling, 2012). This rate rises to 51% for those who indicated they were harassed or bullied at school (and 78% of study participants reported they were harassed at school) (Grant et al., 2012). Many transgender youth are shamed, abused, and kicked out of their family homes, and some are murdered for being transgender.

Historically, it has been common for parents of gender-nonconforming youth to deny their children’s true gender identity and force them to live as their birth gender. Recently, psychologists have put forth a gender-affirmative model, which suggests that adults and parents should follow the lead of children in their gender identity and expressions (Ehrensaft, 2016; Hidalgo, Ehrensaft, Tishelman, Clark, Garafalo, Rosenthal, Spack & Olson, 2013). A recent study has backed the gender-affirmative model by showing that youth who have been affirmed and supported by parents in their gender identity at young ages show depression and anxiety on equal levels with their peers (Olson, Durwood, DeMeules & McLaughlin, 2016). Parents who are supportive are doing what is best for their children. This same support and affirmation should be offered in classrooms and on all school grounds.

BEING OPEN TO POSSIBILITIES: AFFIRMING A CHILD’S AUTHENTIC SELF

Next to their homes, school is the place where most children spend a majority of their time. While supportive parenting is paramount to raising a healthy child, whether gender-conforming or gender-nonconforming, educators are the next step. Educators must be trained on how to communicate and interact with children in a compassionate manner. Of course, very few young children will identify as transgender, gender-nonconforming, or gender variant. Most will be cisgender, identifying their gender as consistent with their biological sex.

Many question the ability of young children to accurately assess their gender identities. However, according to experts, the concept of gender constancy—an individual’s understanding that their assigned sex is constant and is accompanied by expectations related to their gender—occurs as early as 3 years old but no later than 6 years old (Rivers & Barnett, 2011). In other words, children see themselves as a particular gender (or somewhere in between) at an early age and quickly learn the stereotypes and roles expected of them in relation to culturally constructed gender norms.

In his essay, “Gender vs. Sex,” Carl (2012) discusses the often-unintentional reinforcement of existing gender stereotypes. He notes that children quickly learn and actively seek to emulate behavior deemed appropriate for particular genders. We are less concerned with how children themselves choose to separate into groups and play particular games than we are with how educators react to particular situations. As Powell (2008) notes, “Casual cross-gender conversations and cooperation in learning, as well as cross-gender friendships, are commonplace in the many Montessori classrooms [he] visited” (p. 27).

However, he relates several instances where adults sometimes mistakenly set boys and girls against one another in ways that make it hard for them to be close friends, now and when they get older. One way of doing this is with competition—“boys against girls.” Another more common way is with teasing about “liking” someone of the other gender.… Too often this sort of teasing shuts down communication between boys and girls until hormones take over. (pp. 28–29)

Powell rightly asserts that teachers and administrators should “never let gender used as a means of separating or excluding go without comment” (p. 29). For instance, if a child in the classroom states “pink is for girls,” the teacher should use the opportunity for a teachable moment to discuss how colors have been arbitrarily chosen to represent particular genders.

These examples are, of course, used within the context of cisgender children who, due to exclusionary games and gendered language use, tend to fall into a trap of reinforcing gendered stereotypes. However, think of the transgender child who is still transitioning, and who is immediately uncomfortable when lessons and play are structured around gendered groupings. Think to yourself how many times a day educators line up their students or send them to the bathroom by gender. These moments are terrifying for transgender children.

Aside from trying to avoid several long-held assumptions regarding gender, one of the best methods for encouraging diversity and enabling inclusivity is to shift the very language we use, including some taken-for-granted norms of speaking.

PROPER PRONOUNS

One of the most difficult, yet most affirmative, communicative modifications to make when aiming for gender inclusivity is the use of pronouns. Despite their relatively small size (there are few of them compared with other parts of speech), pronouns are an integral aspect of the structure of speech (Key, 2014). Upon first meeting someone, we typically look for visual cues regarding the gender of that person and then use gendered pronouns to refer to them. For a transitioning child, the switch to the correct gendered pronoun is a profound and validating step, and we have personally witnessed children completely change their demeanor when allowed to use the pronouns that best fit their identity. Within the transgender community, it is common practice to introduce yourself by name, then to state the pronouns you prefer. While a cisgender person would likely go along with the pronouns that match gender identity, such as “she, her, hers” or “he, him, his,” transgender individuals may prefer pronouns that match their preferred gender identity but may opt instead to use the more generalized “they, them, theirs.” Still others are going further and creating new pronouns, such as “ze” or “hir” (Key; Teich, 2012).

For the gender-nonconforming child, whose gender identity may be even more complicated, pronouns are particularly tricky. Teachers should ask which pronoun a child prefers. Regardless of whether this student is cisgender, transgender, or gender-nonconforming, using preferred pronouns is a sign of respect toward that child. Teachers having difficulty using correct pronouns may also decide to call each student by their first name. In fact, children transitioning into their correct gender identity often choose new names that are reflective of their preferred identity or names that are gender-neutral. If this is the case, teachers should ask what name the child prefers as well.

POLICY CONCERNS

According to Grossman and D’Augelli (2006), “Exhibiting gender-atypical behavior makes transgender youth an especially vulnerable population” (p. 113), and transgender or gender-nonconforming youth often face significant discrimination in schools. In Grossman & D’Augelli’s study, transgender youth frequently noted a lack of safe spaces. One of the main outcomes of this marginalization has been harassment and outright bullying in school.

MICROAGGRESSIONS

Even with the best of intentions, teachers will often find that they fall into predictable gender patterns. After all, we have been raised in rigid cultural conditions that dictate how we act, interact, and behave. Even when teachers are doing their best to respect the gender of each student, they should also be aware of how the students are interacting with one another. What we accept as “kids being kids” can be extremely problematic, resulting in what are known as microaggressions—the subtle, everyday communications that, often unintentionally, suggest to “a person of a particular marginalized group that who they are is not acceptable” (Ehrensaft, p. 131). Children may question transgender or gender-nonconforming students about a variety of issues. For instance, students may ask transgender peers if they used to be a different sex or what their names used to be. These questions may continue despite the child’s protestations.

Teachers and even parents of transgender children may also fall victim to these subtle nonverbal and verbal interactions. Even one mishandled situation could be detrimental to a child’s mental health and future acceptance among their peers. All interactions must be handled with utmost care, using carefully selected language, to ensure a child is protected from being “outed” or taunted for their authentic gender identity. Slipups do occur, even among those who are well-trained and knowledgeable regarding gender. Acknowledging the mistake and offering a quick apology can go a long way toward showing students the support they need.

GENDER-BASED BULLYING

When these interactions move into more intense (and often intentional) harassment, they enter the realm of gender-based bullying. In many cases, bullying is not reported by transgender students, and if it is reported, often nothing is done to address the wrongdoing. Unfortunately, this sends a message to the student population that bullying a transgender peer is acceptable behavior. This attitude also worsens the isolation and depression many transgender students experience. Students who are physically and/or verbally bullied at school show increased anxiety about school, which may lead them to skip classes, resulting in poor academic performance (Singh & Jackson, 2012).

School administrators should take immediate action if they become aware of any form of bullying, especially if it concerns a transgender student. Schools must adopt a zero tolerance for bullying policy and encourage respect toward all differences. Additionally, schools should offer a safe place where a student can always retreat if something inappropriate occurs. For instance, a school nurse’s office or an administrator’s office can serve as a “safe zone,” where gender-nonconforming students can go if they feel threatened or simply need a place to hang out for a while. Educators and administrators must take seriously these issues by resolutely condemning any harassment on the basis of gender and holding accountable any students who engage in gender-based bullying.

BATHROOM ANXIETY

One of the most visible controversies surrounding transgender rights has been the use of bathrooms. We suggest that gender-nonconforming children should always be encouraged to use the bathroom they feel most comfortable using (Key, 2014). Many states do not offer legal protections like California’s AB 1266, which assures transgender students full access to participate and achieve success in school, including using the restroom of their gender identity, “regardless of their status in official school records or their sex assigned at birth” (Anonymous, 2014). In those cases without specific protections, administrators may suggest transgender students use a separate restroom, marked specifically as unisex, such as the staff restroom or nurse’s office restroom. While this may seem like an easy compromise, it risks potentially “outing” the student as different and is an example of unfair and unequal treatment.

Given the current political climate, teachers and administrators should be prepared for some parents to take issue with the restroom usage of a transgender student. In some cases, this is couched as an affront to their cisgender children. Restrooms have been a source of disagreement among the population who believe being transgender is a choice. We have seen numerous cases where individuals have created scare tactics to make it appear that transgender individuals are predators and should use the restroom corresponding to the gender listed on their birth certificates. However, the facts show otherwise: Most gender-nonconforming and transgender individuals are extremely concerned about their privacy, and, to date, there have been no documented situations in which transgender individuals have taken advantage of or have acted inappropriately in the restroom (Percelay, 2015). Moreover, many transgender youth are so uncomfortable using the restroom that they withhold the urge during the school day, and, as a result, develop urinary tract and/ or kidney infections (Brill & Pepper, 2008). Fortunately, both male and female restrooms are required to have a private toilet stall, where the user can lock the door and be alone while they use the facilities, which should ease many concerns. Regardless, it is important to ask individual students what they are most comfortable with and support them with the option that is best for them.

REVISITING POLICY LANGUAGE

It is up to Montessori schools to ensure that, along with sexual orientation, gender identity and expression are considered protected categories within school nondiscrimination and antiharassment policy. Without such policies, schools lack the ability to intervene in difficult situations. For instance, with a lack of clear guidelines, a case of gender bullying will likely result in interventions that are “remedial, reactive, and lack foresight and intentionality” (Singh & Jackson, p. 177). In regard to language, are your policies written in such a way that they include, value, and protect transgender and gender nonconforming students? Ungerer (2013) urges us to be mindful of using inclusive language and imagery within school communications and public relations work.

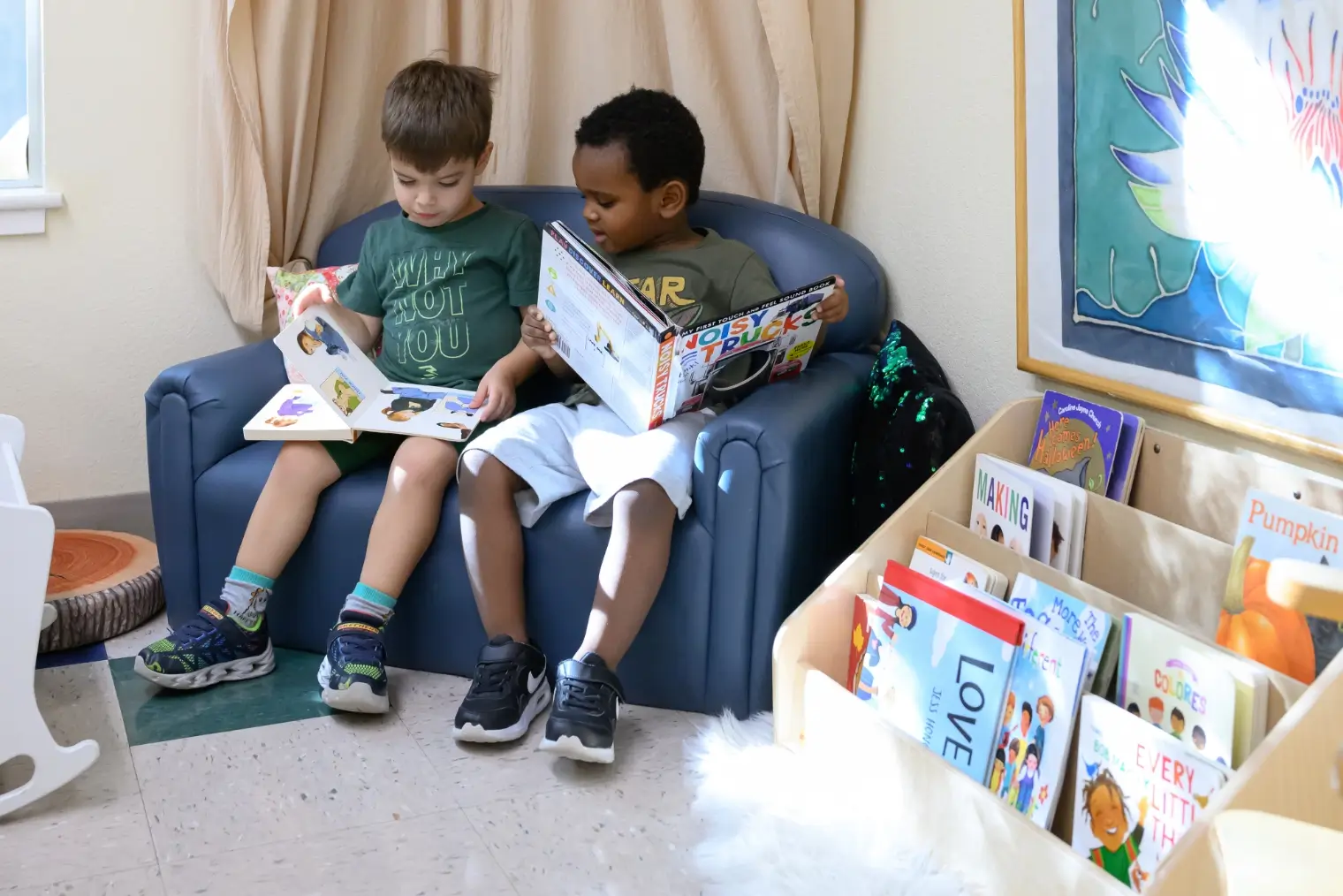

Of course, there are many additional ways that Montessori schools can broaden the values of inclusivity, diversity, and respect to include gender identity. Hold regular training sessions for educators, administrators, and counselors on transgender issues and terminology. Broaden the selection of materials you assign to students, such as including books from a growing body of work that highlight gender-nonconforming themes (see Suggested Materials for Young Children, at right). Incorporating these changes into the Montessori culture and curricula will increase visibility and set the tone for a safe and supportive learning environment.

Lest you think implementing these suggestions will affect only a small minority of students, what we are suggesting will in fact benefit all Montessori students, educators, and administrators by providing the basis for understanding gender. Despite a strong desire among educators to be inclusive and understanding of gender-nonconformity, the ability to enact communicative strategies for interaction is often difficult. From a practical standpoint, teaching and practicing diversity and acceptance should alleviate future problems. It should not be your role to assess the student or to figure out the causal links to the child’s gender identity. Instead, consider it your job to be supportive of a child’s questions and assertions regarding gender.

About the Author

CHARLES GOEHRING, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Communication at San Diego State University. His research incorporates the study of gender and communication and rhetoric. Contact him at cgoehring@mail.sdsu.edu.

HILLARY WHITTINGTON is the mother of a transgender child, a transgender rights activist, and the author of Raising Ryland: Our Story of Parenting a Transgender Child with No Strings Attached (HarperCollins, 2015). Contact her at hillary@thewhittingtonteam.com.

References

Anonymous. (2014). Transgender youth and access to gendered spaces in education.

Harvard Law Review, 127(6): 1722.

Brill, S. A. & Pepper, R. (2008). The transgender child: A handbook for families and professionals. San Francisco: Cleis Press.

Carl, J. (2012). Gender vs. sex: What’s the difference? Montessori Life, 24(1), 26–30.

Ehrensaft, D. (2016). The gender creative child: Pathways for nurturing and supporting children who live outside gender boxes. New York: The Experiment.

Grant, J. M., Mottet, L. A., Tanis, J., Harrison, J., Herman, J. L. & Keisling, M. (2012). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Grossman, A. & D’Augelli, A. (2006). Transgender youth: Invisible and vulnerable.

Journal of Homosexuality, 51(1), 111–128.

Hidalgo, M., Ehrensaft, D., Tishelman, A., Clark, L., Garofalo, R., Rosenthal, S., Spack, N. & Olson, J. (2013). The gender affirmative model: What we know and what we aim to learn. Human Development, 56(5), 285–290.

Key, A. (2014). Children. In L. Erickson-Schroth (Ed.), Trans bodies, trans selves: A resource for the transgender community (419–445). New York: Oxford University Press.

Olson, K., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M. & McLaughlin, K. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3), 1–8.

Percelay, R. (2015, June 3). 17 school districts debunk right-wing lies about protections for transgender students. Media Matters for America. www.mediamatters.org/ research/2015/06/03/17-school-districts-debunk-right-wing-lies-abou/203867.

Powell, M. (2008). Gender play and good governance. Montessori Life, 20(1), 26–29. Rivers, C. & Barnett, R. (2011). The truth about girls and boys. New York: Columbia

University Press.

Singh, A. & Jackson, K. (2012). CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Queer and transgender youth: Education and liberation in our schools. Counterpoints, 367, 175–186.

Teich, N. M. (2012). Transgender 101: A simple guide to a complex issue. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ungerer, R. A. (2013). The role of diversity and inclusion in Montessori education.

Montessori Life, 25(1), 3–7.

Suggested Materials for Young Children

Hall, M. (2015). Red: A crayon’s story. New York: Greenwillow Books.

Herthel, J., Jennings, J. & McNicholas, S. (2014). I am Jazz! New York: Dial Books for Young Readers.

Hilton, P. & Hill, J. (2011). The boy with pink hair. New York: Penguin/Celebra.

Kilodavis, C. & DeSimone, S. (2011). My princess boy: A mom’s story about a young boy who loves to dress up. New York: Aladdin.

Parr, T. (2015). It’s okay to be different. New York: Scholastic.