Walking into a well-prepared Montessori environment, one notices the purposeful arrangement of materials on the shelves. The arrangement is not arbitrarily aesthetic, although the materials themselves are beautiful and inviting. The materials on any given shelf are arranged from left to right, top shelf to bottom, in the order they will be presented to and used by the child. Mastery of one material enables moving onto the next, as “each material was developed in the context of all the other materials.” Children only use a material once they have mastered the one that precedes it in carefully designed sequences.

In the sensorial area of the Early Childhood (EC) classroom, for example, we find a series of materials designed for the study of dimensionality—length, width, and height. These include the Solid Cylinders; the Pink Tower; the Brown Stair; and the Red Rods. As explained by Angeline Lillard, “the Solid Cylinders (or Solid Insets) set in motion thinking about changes in dimension, leading to the Pink Tower with three changing dimensions, then the Brown Stair with two, then the Red Rods with just one.” In addition to refining their visual discrimination of dimensionality, the child using these materials strengthens hand-eye coordination and fine-motor movements, all while practicing concentration and precision.

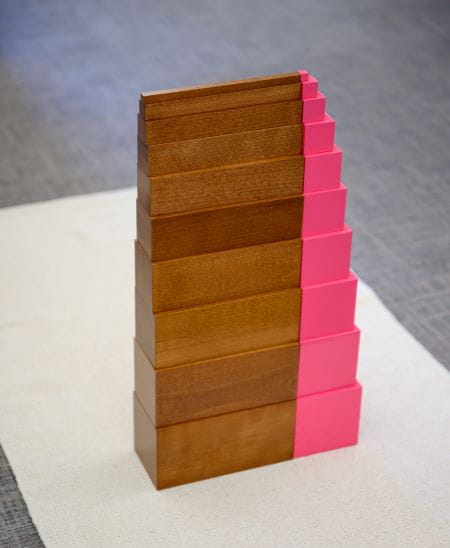

In an earlier piece, we presented the Pink Tower and discussed how the physical design of the material incorporates pedagogical properties that contribute to the child’s physical and academic development. Here we examine the Brown (or Broad) Stair with the same focus, while also comparing and contrasting its properties with those of the Pink Tower.

Physical Properties

Like the Pink Tower, the Brown Stair consists of ten prisms, but these are rectangular rather than cubic. And while the pieces of both materials increase in size one cubic centimeter at a time, the pieces of the Pink Tower increase in size in three dimensions, while those of the Brown Stair increase only in two. Each prism is 20 centimeters long, with the width and height increasing incrementally by one cubic centimeter. For example:

- the first prism is 20 cm x 1 cm x 1 cm

- the second prism is 20 cm x 2 cm x 2 cm

- the third is 20 cm x 3 cm x 3 cm …

- … the tenth prism is 20 cm x 10 cm x 10 cm

Continuing with the math, we see that the second prism is exactly four times larger than the first prism; the third prism is nine times larger than the first; and so on, up to the tenth prism, which is exactly one hundred times larger than the first. In other words, the prisms get proportionally larger according to the sequence of square numbers. This is, of course, not an accident. Recall that the Pink Tower pieces increase in size according to the sequence of cubic numbers. The second cube is the same size as eight of the one-centimeter cubes (2 cm cubed); the third cube is equivalent to twenty-seven cubes (3 cm cubed); … the tenth cube is equivalent to one-thousand cubes (10 cm cubed).

Like the Pink Tower, the difference in size between the prisms of the Brown Stair represents the “isolation of difficulty.” As a Montessori term, this refers to a single attribute of the material or work on which the child focuses their attention. And having differences in only two of the three dimensions increases the challenge level of the Brown Stair over that of the Pink Tower.

Pedagogical Properties

Pedagogically speaking, both materials embody mathematical properties that directly promote skills in visual discrimination, seriation, and counting from one to ten. The proportional difference in size between the individual pieces may have a role, albeit a less direct one, in preparing the child for future work in mathematics and geometry, such as the study of squared and cubed numbers. This is known as indirect preparation, or “the deeper educational purpose of many Montessori activities … remote in time.” According to Montessori, for example, as the child works with the Brown Stair on a sensorial level, the groundwork is being laid for future work involving the same mathematical properties, but at a more sophisticated and abstract level.

We argued in an earlier piece that “it is difficult to [measure], in contemporary neurocognitive terms,” the mechanisms involved in and the effects of indirect preparation. The young child who works sensorially with the Pink Tower or Brown Stair does not have an understanding of the mathematical properties inherent in these materials, and the extent to which these early experiences impact future understanding cannot presently be empirically tracked.

Nevertheless, the pedagogical value of these materials is not diminished by these facts. In addition to the mathematically related skills of counting, seriation, and visual discrimination of dimensions, both materials involve fine-motor practice, which help build the muscular coordination skills necessary for writing. Additionally, the use of comparatives and superlatives to describe the individual pieces increases the young child’s vocabulary. The Brown Stair, therefore, like the Pink Tower, is an important foundational material for both sensory and academic education.

It is also important to note that these sensorial materials are often used again as mathematics or geometry materials in the Elementary classroom for the study of volume and surface area. The reappearance and repurposing of these “old friends” is one aspect of the spiral curriculum, wherein children revisit “basic concepts and major themes from all curriculum areas, from the Early Childhood level to Secondary studies, each time delving deeper and cementing their understanding.”

Working with the Brown Stair

When presenting the Brown Stair, the guide shows the child how to carefully remove one prism at a time from the shelf, given the following guidelines (slight variations are to be expected, depending on one’s training):

- Hold the thinner prisms by grasping the top at the center, using the thumb and fingers.

- Hold the thicker prisms with one hand underneath for support.

- Carry each prism at waist level, holding it in a vertical position.

- Carry the prisms, one at a time, from thinnest to thickest, to the work mat.

Once the prisms have all been moved to the mat and placed in random order, the guide:

- places the thickest prism at the back left corner of the mat, using two hands (adding a visual element to represent the prism’s heft)

- selects the next thickest prism, using two hands, and places it under the thickest prism so that the edges are aligned

- checks the alignment by sliding a hand along the left side of the two prisms

- continues by placing the remaining prisms in the correct sequence, bringing the pieces closer and closer to the front of the mat

When complete, the guide dismantles the arrangement, beginning with the thinnest prism, and placing each piece in a random spot on the right side of the mat. The child is then invited to build the Brown Stair independently, repeating as often as desired.

An extension to the original building exercise involves using the thinnest prism to demonstrate that each prism is exactly one centimeter higher than the one preceding it. By placing the thinnest prism atop the second-thickest prism, and up against the thickest prism, the child sees that both prisms are the same height at the position of the thinnest prism. This gets repeated with every prism, descending the stair. This particular extension is consistent with the original aim of visual discrimination of changing dimensions. Other extensions, however, may not be in alignment with the purpose of the Brown Stair, raising questions about their appropriateness.

Considering Other Extensions

There are a range of extensions that the child may discover for themselves, some more constructive and appropriate than others. Consider the following possibilities:

- A child realizes “that two sides of the blocks of the Brown Stair are equal in dimension to the sides of the cubes of the Pink Tower, lining the two materials up side by side to explore this realization.” (Lillard)

- A child combines pieces of the Brown Stair with those of the Knobless Cylinders to build towers. (Lillard)

- A child uses the blocks of the Brown Stair to build a house. (Lillard)

The guide may view the first instance “as a wonderful discovery” on the part of the child, and encourage this alternative use of the materials. The child is, after all, continuing to explore dimensionality. The extent to which the child is exploring dimensionality in the second and third examples is less systematic, as they need only determine that one block is large enough to support another. The alternative use of materials may or may not “engender important learning,” about which Lillard makes the following important point:

The fact that Montessori teachers sometimes embrace variation in use can complicate teaching. They must decide on the spot if a child’s alternative use of the material is constructive. If the variation seems constructive, the teacher will not interfere; if the teacher decides the child’s varied use is not constructive, she represents the material’s proper use to the child.

In the same article, Lillard addresses “playful learning” in Montessori classrooms, including a discussion of three reasons for limiting the ways in which children can use the materials:

- Each material has a specific aim. “Playing freely with materials that have a symbolic purpose can interfere with children learning the specific purpose.” Building a house with the blocks of the Brown Stair, for example, does not serve the purpose of systematically exploring dimensional change.

- Restricting the use of materials to their intended purpose helps preserve order. “That the Montessori method calls for a specific orderly way in which to interact with the materials probably in itself contributes a sense of order in a classroom.” Using the materials in myriad ways may disrupt this classroom order.

- Using the materials only in ways they have been shown may contribute to a child’s increased cognitive executive functioning. According to Lillard’s own studies, “Children in classic Montessori classrooms excel in executive function compared to children in looser Montessori classrooms and in conventional classrooms.” This enhanced executive capacity could result from the child’s self-restraint regarding other ways of interacting with the materials.

An interesting question proposed by Lillard concerns whether alternative uses of a material impact the intended long-term benefit of that material. We have already described the idea of indirect preparation, and how materials like the Pink Tower and Brown Stair embody advanced mathematical concepts that the child will encounter in their later years. Lillard looks at the question from a different angle, asking, “If children can build houses with the Brown Stair, does it impede their progress in the activities—say, math—that eventually follow?” As Lillard suggests, this may be an interesting topic for empirical study.

We may not be able to measure the degree to which using the Brown Stair prepares the child for later work in mathematics and geometry, nor whether alternative uses of the material impedes the child’s progress in these areas. We do know that, like the Pink Tower, the Brown Stair promotes a number of skills associated with the mathematical mind—visual discrimination, seriation, and precision. Additionally, the decimal system is reinforced, new vocabulary is introduced, and the child practices fine-motor skills and concentration. As one material in a carefully designed sequence, the Brown Stair represents a step in the child’s journey toward mathematical understanding and discovery.

Reference

Montessori Primary Guide, Visual Sense – Presenting the Brown Stairs

The opinions expressed in Montessori Life are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of AMS.