“DEVELOPMENT IS A SERIES OF REBIRTHS.”

Maria Montessori, The Absorbent Mind, p. 132

This article was featured in our 2024-2025 Winter edition of Montessori Life magazine. Read the full issue online (AMS members only).

AMS members also receive a print subscription to Montessori Life magazine. Become a member today to receive your own subscription plus access to the complete digital archives.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Mothers, more than other caregivers, are often expected to have instant capability for caregiving. However, statistics on maternal mental health and mortality demonstrate that birthing mothers in the United States are in crisis. These facts are related and require our attention. But “mothering,” as I describe it, is not exclusive to cisgender women. All caregivers have the potential to experience significant development and transformation, regardless of sex, gender, or their path to parenthood.

Christine Carrig

THE MOTHER MADE A BEELINE FOR ME. I was hosting a back to school night at the Montessori school I’ve run in Brooklyn for 14 years. She wore a look of urgent exasperation—a look I’ve seen many times on the faces of mothers who hope that, between my professional expertise with children and my experience as a mother of four, I will have the answers they need.

“I will sleep again, right?” she asked, after describing how she felt herself coming unraveled from the exhaustion and relentless demands of caring for an infant and a toddler. “Eventually I will feel like myself again, don’t you think?”

She seemed so full of desperation that I felt the need to reassure her in the affirmative. All the while, I knew the truth: The version of yourself you will meet on the other side of sleep will not be the same person you knew before you had children.

As Chelsea Conaboy, author of Mother Brain: How Neuroscience Is Rewriting the Story of Parenthood, succinctly puts it, the transition to motherhood “is a process—one of short-term upheaval and long-lasting change. Overwhelming and purposeful” (2022, p. 49). The mother at my school was experiencing short-term upheaval requisite to the transformation she was undergoing. What she would find on the other side was long-lasting change. The desperation she felt came, at least in part, from the fact that no one had told her that this acute stage of adult development was, in addition to being profoundly purposeful, inevitably overwhelming. Sound familiar?

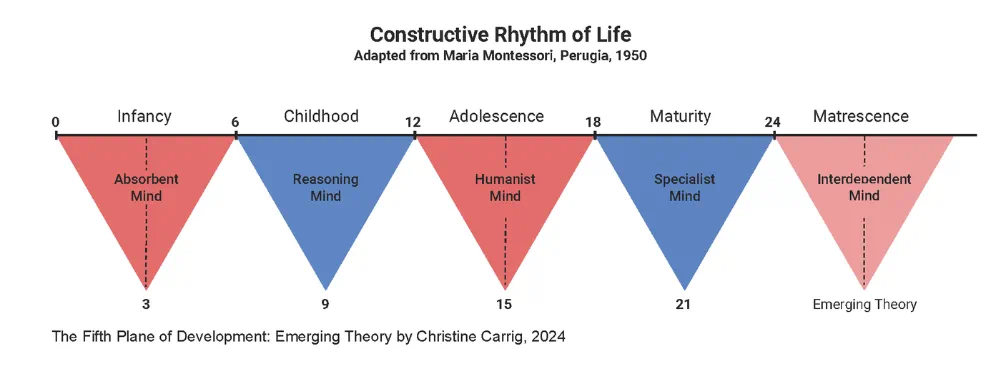

In 1951, when Maria Montessori described the pattern of human development as the Constructive Rhythm of Life, marking each of four chapters or planes of development with an inverted triangle, she colored the first and third planes red to represent their intensity (Grazzini, 1996). These two red triangles are referred to as creative periods and represent early childhood and adolescence, times of life that involve intense development and rapid brain changes (Goddings & Giedd, 2014). Blue triangles mark the second and fourth planes of development, representing the more stable growth of the elementary school years and the relative maturity of early adulthood.

“Societally speaking, “the empathetic thrust favors the predicament of the child, not the caretaker of the child,” resulting in hyperfocus on one side of the parent-child dyad.”

Today, neuroscientists have confirmed what Montessori astutely observed: that the red creative periods involve structural and functional brain changes that create temporary upheaval in exchange for a more efficient brain to emerge, finely tuned for the next stage of life (Goddings & Giedd, 2014; Grazzini, 1996). Beyond adolescence, the third plane of development, lies the calmer waters of maturity—the fourth plane. While development is known to continue into adulthood, it has largely been thought that, as adults, we are no longer thrust into the destabilization of rapid pruning and tuning that marked our first and third planes of development. But what if there is an event that could precipitate a fifth plane of development, and a third and final creative period? An acute phase of adult development spurred by the need for an entirely new set of skills, necessitated by an entirely new set of priorities? This is what the mother at my back to school night was experiencing. I too experienced it, several times over, before I had words to describe it.

FINDING MOTHERS ON A DEVELOPMENTAL MAP

When I became pregnant with my first child, in 2011, the sentiment among the parents at the school I led was that, given my extensive education in child development, as well as my many years of experience with children, new parenthood would be a walk in the park for me. Nothing was further from the truth.

Knowing about the developmental trajectory of children did little to prepare me for the developmental trajectory I felt myself thrust into. In fact, I had never even heard of the concept of maternal development. And yet, while pregnant and after my children were born, I experienced changes across every domain of my existence. Reva Rubin, a specialist in maternity nursing and a theorist who introduced the concept of maternal role attainment, describes the transition to motherhood as being “an exchange of a known self in a known world for an unknown self in an unknown world” (Rubin, 1984, p. 52). My unknown world began with the physical changes I underwent in pregnancy and continued in all areas of my life well after my children’s births. I experienced relational changes with friends and family as my priorities shifted. I found myself in uncharted emotional territory; I would swing between blissed-out-unity with my baby and a frustrated form of grief as I both clawed for and mourned my long-lost autonomy. I experienced “mommy brain” in the sense that my cognitive capacities often felt like they were eluding me. While I had heard of some of these changes spoken about in a patronizing manner by family members, friends, and in the media, I had never understood them to be anything but a nuisance factor.

Still, according to my education, the only development that needed support, validation, and recognition was that of my children. This notion is based on decades of developmental research that goes to great lengths to map the child’s development but assumes parents are relatively stable in their own formation and development (Athan & Reel, 2015). Societally speaking, “the empathetic thrust favors the predicament of the child, not the caretaker of the child,” resulting in hyperfocus on one side of the parent-child dyad, while leaving the other largely unexamined (Thurer, 1993, p. 519).

There is so much that Maria Montessori got right. She brilliantly and accurately mapped out the child’s development from birth through maturity. Throughout her writings, she draws parallels between early childhood and adolescence as delicate and difficult inflection points, marked by huge physical and developmental changes that are ripe with both opportunity and vulnerability. In her time, Montessori fought for the needs of young children to be recognized and supported, and she emphasized the need for parents to become better educated regarding their children’s development. But the extremes with which she characterized the roles of children and adults—perhaps necessary to right the perceived wrongs of society in her day—also had the unintended effect of pitting parents and children against one another.

Reading Montessori’s texts closely, it seems it was difficult for her empathy toward children to not interfere with the way she perceived the adults in relation to them. In fact, the idea of adults being an acrimonious force or hindrance in their child’s life, unless they make great effort to “find within [themself] the still unknown error that prevents [them] from seeing the child as he is,” is pervasive throughout Montessori’s writings (Montessori, 1972, p. 11). In The Child in the Family, describing the parent in relation to the child, Montessori says a parent often “suffocates the child’s natural impulse to act,…impedes the child’s ability to live, to do anything useful, to exert great energy” (Montessori, 2020, p. 49). In the same chapter, she goes on to say that a child’s rebellion toward a parent is justified: “Certainly an adult would not behave differently toward an enemy who, penetrating the sanctuaries and daring to lay down laws, came to crush the will of the conquered and unarmed” (Montessori, 2020, p. 49). As has been the case with many educators and psychologists who advocate for optimal circumstances for the child, it is often hard to view the parent-child dyad as a symbiotic relationship in which each member’s success means the other also succeeds. More often, the child is viewed as a potentially optimal being, or as Montessori puts it, “more innocent and pure,” while the parent tends to be described as an agent who is constantly choosing whether to facilitate development or thwart it (Montessori, 2020, p. 50). Montessori was not alone in this splitting of the parent-child dyad into dichotomies of “good” or “flawed” but was rather a part of a larger movement of psychologists and child advocates who were likely spurred by Freudian ideas to blame parents, and mothers in particular, for the psychological suffering of children (Dolnick, 1998). Still today, it is rare to view a parent’s imperfection in relation to their child as anything that warrants further inquiry; instead it tends to be viewed as something that warrants judgment.

While much of the study of development seems to focus primarily on the development of the child, there are a few psychologists who notably continued their studies of human development into adulthood. Erik Erikson’s concept of the stages of psychosocial development, articulated in the late 1950s, was significant in that it included development through the entire human lifespan, though still made no distinction in adult development based on the need to adapt to parenthood (Orenstein, 2022). Notably, Erikson trained and received his Montessori certification at the Maria Montessori School in Vienna prior to undertaking his training at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. His theories consider the social context of development, likely influenced by his Montessori training, which considered the environment as a critical component in the child’s development.

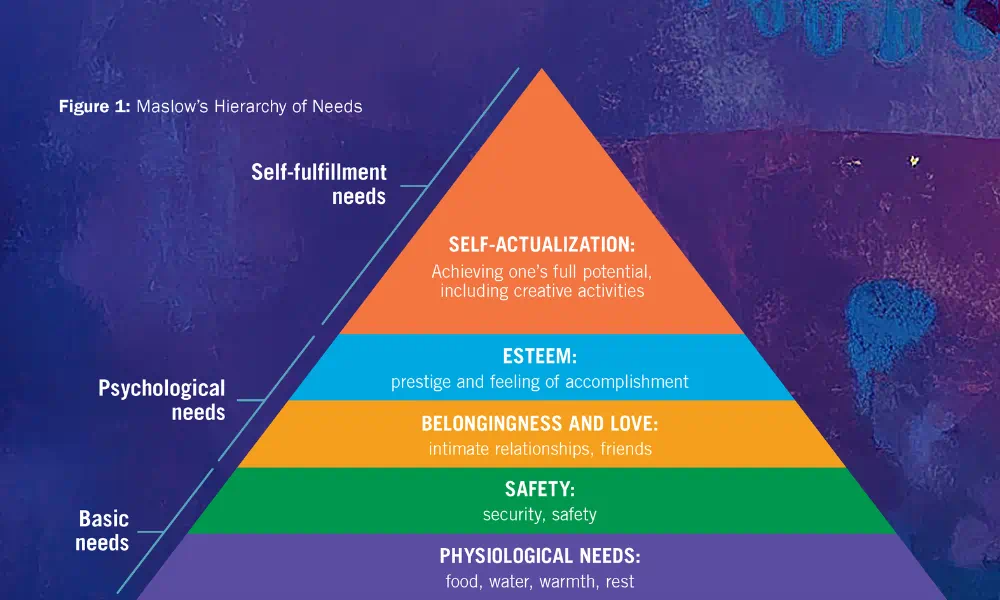

In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (see graphic above), self-actualization is the highest tier of the pyramid, and one can presume that self-actualization is typically occurring in mature adults. However, we see no exceptions made for the mother who may find herself self-actualized while simultaneously being thrust to the bottom of the hierarchy of needs, lacking sleep, finding little time to feed herself, and feeling unfamiliar in her own postpartum body (Trivedi, 2019; Athan & Miller, 2005). These juxtapositions of new parenthood are not easily pinned down, which could be considered as an innocuous part of the reason maternal development has only recently begun to be studied in earnest.

Another reason, perhaps so obvious that it is lost in plain sight, is that once a mother transitions into motherhood, she is no longer seen as an individual. The mother is inextricably linked to her infant, as the infant is, in turn, inextricably linked to its mother. Throughout decades of study of child development, mothers have been identified as objects in the developmental trajectories of their children, yet have continually been overlooked as subjects in their own developmental trajectory (Athan & Reel, 2015; Athan, 2024). In other words, the study of mothers largely views them as “an undefined entity, singularly placed in the world with one goal only, the understanding and satisfaction of the needs of the child” (Bernardez, 2003, p. 300). While it has been acknowledged that mothers often experience heightened distress as a result of their transition to motherhood, so far the only solution our society has been able to offer mothers is the suggestion that they seek therapy or medication to “fix” the upheaval that is often precipitated by a need to rapidly and profoundly adapt to their new role. In other words, pathologizing the maternal experience has largely funneled mothers to the clinical realm, and notably excluded them from the developmental realm. In relegating mothers’ distress to strictly a diagnosable condition, there is a missed opportunity to look at their stage of life as “a maturational ‘crisis’ with its requisite upheaval, demanding adaptation, much like any other critical turning point in a human life” (Athan & Reel, 2015, p. 318).

My own experience of motherhood and the experiences of mothers I’ve worked with over the course of nearly two decades have demonstrated that mothers indeed enter into a unique developmental stage that cannot be relegated to tidy dichotomies of success or failure, mental health or mental illness (Athan, 2024;Athan & Reel 2015). Search as I may, I could not find a theory that considered the early years of motherhood to be unique in their developmental trajectory until Imet Dr. Aurélie Athan, clinical psychologist and professor at Teachers College, Columbia University.

In a pivotal paper entitled “A Critical Need for the Concept of Matrescence in Perinatal Psychology, ”Dr. Athan writes, “There exists an urgent need for a strengths-based framework that studies the normative aspects of a mother’s self-development and acknowledges both the positive and negative outcomes with equal consideration” (Athan, 2024). Pathologizing a mother tends to highlight the negative outcomes of herown development. By contrast, viewing a mother in a positive light only when she is optimally meeting the needs of her child eclipses her subjectivity. A developmental framework, inclusive of the varied experiences of mothers, is needed to bring mothers into full view.

“MATRESCENCE, LIKE ADOLESCENCE”

In the 1970s, American anthropologist Dr. Dana Raphael coined the term matrescence to refer to the developmental transition that mothers enter into upon giving birth (Raphael, 1975). (Incidentally, Raphael also coined the term doula in reference to the person who supports a mother so that she might support her infant.) In recent years, Athan has been responsible for reviving matrescence, taking it beyond the field of anthropology and into maternal mental health as a way to complement the largely diagnostic focus by using a lifespan developmental approach to expand our thinking of mothers. In doing so, Athan has expanded the scope of matrescence to be holistic and all-encompassing of the ways in which mothers experience profound developmental shifts across multiple domains.

In 2010, Athan began to use the slogan “Matrescence, like adolescence” in her work to spread the word about the developmental transition mothers experience. Likening the two developmental transitions, matrescence and adolescence, helps mothers and non-mothers alike remember the wide-reaching changes that take place within us and around us as we make the transition from childhood to adulthood. Athan continues to examine whether matrescence is simply the transition from non-mother to mother, or from mother of one child to more, and when it begins or even ends. Athan expanded the definition of matrescence to encompass changes across all life domains: physical, relational, psychological, social, economic, political, moral, and even spiritual (Athan, 2024).Finally, she is clear that mothers can enter this stage of development through pregnancy, surrogacy, adoption, fostering, stepparenting, or otherwise. Regardless of how one enters motherhood, they will be shaped by it.

“Just as the hormonal and psychological changes of adolescence prepare a person for successful adulthood, matrescence is a time when the brain and body prepare for the transition to motherhood,” a group of researchers who study the maternal brain wrote in an article published in the journal Trends in Cognitive Sciences (Orchard et al., 2023, p. 302). “These two life stages are characterized by shifting social roles, with adulthood marking the social transition from dependence to independence, and motherhood marking the transition to now supporting one’s own dependents” (Orchardet al., 2023, p. 302). However, unlike adolescence, matrescence can be experienced again and again, with each child a mother has. The reason for this seems logical if we stop to consider the genius of nature. “The peripartum period represents one of the most neurobehaviorally plastic phases in a female’s life,” a group of researchers wrote in a 2022 review published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews (Pawluski et al., 2022, p. 3). This brain plasticity will repeat with the arrival of each baby so that the mother can remain uniquely attuned to the stimuli of that particular baby. As parents and educators know, no two children are the same, even siblings, so the malleability of the maternal brain in pregnancy and the postnatal period allows the mother to be highly adaptive to each child (Pawluski et al., 2022; Athan, 2024).

Matrescence, when mapped onto Montessori’s Constructive Rhythm of Life, shows striking similarities to the previous two creative periods. Neuroscience shows us that matrescent mothers undergo another round of brain pruning and tuning, which allows them to rapidly adapt to their new and demanding role as parent. The idea that the brain changes during matrescence represent a preparation for parenthood that “is in line with numerous events occurring during other developmental stages such as early childhood or adolescence where decreases in neurogenesis [new neurons forming in the brain] and synaptic pruning are well-known to be necessary for healthy behavioral outcomes,” researchers, led by neuroscientist Jodi Pawluski, wrote (Pawluskiet al., 2022, p. 3). As a lifelong Montessorian, what this research shows me is that matrescence appears to be a distinct fifth plane of development, as well as the third creative period. Understanding that all development unfolds within the context of an environment, I am als ocompelled to examine what that environment is for mothers today.

CONSIDERING MOTHERS IN A SOCIAL CONTEXT

In order to experience rapid adaptation, all living creatures must also become increasingly sensitive to their environment so they can adapt in a purposeful, productive, and responsive manner. Montessori says that if the child is absorbing the environment in such a profound way, we must consider “what kind of environment to make, if we want to help the child” (Montessori, 1995, p. 102). Montessori repeatedly suggests that child development is a matter of social importance and social responsibility, understanding that a child’s interaction with their environment will have a critical impact on either optimal or suboptimal development (Montessori, 1995).

If we know development of the child is inextricably linked to the mother, and if we also know that the child’s environment plays a critical role in their development, then perhaps we can consider the treatment of both child and mother as a matter of social importance. Accepting this to be true, the mother’s environment, and all it encompasses, should be a top priority to us as educators and champions of holistic development. We have only to look at statistics on maternal mental health and maternal mortality to see that the environment, particularly in the United States, is far from supportive of maternal development. Today in the United States, the single leading cause of maternal death during pregnancy or within the first year postpartum, as reported by both the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is suicide. According to the CDC, 80% of maternal deaths are preventable. The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Psychiatry shows that an estimated 15–21% of mothers will experience a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD), with barriers to health-care services that disproportionately impact Black mothers (Kozhimannil et al., 2011).

“If we know development of the child is inextricably linked to the mother, and if we also know that the child’s environment plays a critical role in their development, then perhaps we can consider the treatment of both child and mother as a matter of social importance.”

It should come as no surprise that the U.S., with the most limited family support policies of all industrialized countries, is also persistently the country with the highest maternal mortality rate. Despite maternal mortality being unacceptably high across all races, it must be noted that Black mothers are dying at twice the rate of white mothers (Chzhen et al., 2019). While the U.S. spends more on health care than any other high-income country, our maternal health and maternal mortality outcomes are demonstrative of the fact that we are not investing in maternal care, nor are we doing enough to ensure equitable access to care (Gunja et al., 2024).

While it’s important to paint a stark picture of the maternal mental health and maternal mortality crisis as well as increase awareness of PMADs, viewing mothers solely through a psychological lens has the potential to pathologize a typical though challenging transition and puts the onus on the mother to seek treatment. Additionally, “concern with mother’s mental health is not entirely altruistic but linked to the mother-child dyad and its influence on child outcome—once again mothers are studied as mediators of development, this time of their young’s own risk for psychopathology” (Athan & Reel, 2015, p. 313). As Katherine Paradice points out in an article for the British Journal of Midwifery, “there is no satisfactory terminology to describe the condition” of mothers feeling a pervasive sense of overwhelm as they adapt to motherhood; she suggests we consider taking “the problem out of the clinical realm of influence into the social realm where it truly belongs” (Paradice, 1995, as cited in Winson, 2017, p. 154).

While it is clear that larger systemic failings must be addressed, even within our schools we can begin to turn the tides by offering families the much-needed developmental framework of matrescence. In a country that clearly does little to value mothers on a policy or practical level, schools that serve young children can fill a critical need for new mothers who are eager to be understood and supported. In the summer of 2024, the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, wrote an opinion piece in the New York Times declaring parental stress a public health crisis, stating, “Something has to change. It begins with fundamentally changing how we value parenting, recognizing that the work of raising a child is crucial to the health and well-being of all society” (Murthy, 2024). As Montessorians, we are uniquely poised to show parents how much we value their crucial work in raising children and also educate them, not only about their child’s development, but also their own. After all, “an education capable of saving humanity is no small undertaking” (Montessori, 2019, p. 30). We are long overdue in recognizing that both children and their parents are part of humanity, both deserving of an education that supports their full flourishing.

UNDERSTANDING AND SUPPORTING MATERNAL DEVELOPMENT

In a recent conversation with Dr. Athan, I recounted to her the well-known story of Maria Montessori walking into a room after mealtime for children at the psychiatric clinic within the University of Rome. I explained that one of the orderlies who accompanied Montessori reacted with disgust to the children throwing themselves on the floor to grab for crumbs, but Montessori herself understood that the children were using the crumbs for sensory stimulation in another wise sensory-deprived environment. Montessori did not see a problem inherent to the children or their actions; she saw a problem with the environment and the utter lack of stimulation and support it provided. She famously and fortunately saw what others could not yet see—unmet needs resulting in thwarted potential—and she set about to meet those needs, and, in doing so, freed children’s potential. Dr. Athan immediately saw the parallel between the progress that’s been made in the last several decades in supporting children across the developmental spectrum and the progress we, societally speaking, have yet to make in supporting mothers. Discussing the utility of offering the framework of matrescence to mothers, she explained, “We want to shift our gaze—to be both close up, seeing the individual mother in front of us who deserves full subjectivity, and to step back and see them embedded in an ecosystem that may or may not be meeting their needs” (personal communication). Placing the mother on the developmental map is the first step in allowing us to see her as an individual in her own right and also as an individual functioning in an environment that she is highly sensitive to because of the critical stage of development she is experiencing.

Given persistent barriers to health-care services in the United States, many of which disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority groups, education becomes a critical preventive and supportive measure, as it can be implemented wherever mothers have already formed community ties (Athan & Carrig,2023). Schools that serve infants, toddlers, and primary students are a great place to start. As Montessori says, “If education is to be based on what we know of little children, we must first understand their development”(Montessori, 2012, p. 42). The same notion should hold true in supporting development of human beings throughout their lifespan.

The table at right describes maternal development in a concrete and practical way, based on several domains, and offers actionable ways to support mothers. This is meant to be more of a guide than a to-do list, so please use it as a way to come to your own insights about how your school or program can practically support mothers in your community.

| MATERNAL DEVELOPMENTAL DOMAINS | ACTIONABLE ACCOMMODATIONS |

|---|---|

| Neurological: Matrescence is a time of heightened neuroplasticity, making this an optimal time for matrescence education. Helping mothers understand and appreciate their own development “challenges the derogatory concept of ‘baby brain.’” (Athan, 2024) | In addition to parent education events that focus solely on the child’s development, educators of babies and young children have an opportunity to introduce mothers to the concept of matrescence and educate them about their own development. You can even share this article with them! |

| Psychological: As mothers adapt to their new role, the “mental load” they carry can feel burdensome and overwhelming. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders impact 15–21% of mothers, as reported by JAMA Psychiatry. | Look for ways to lighten the mental load for mothers to the extent that is reasonable. In addition to posting resources related to child health and development, normalize including resources for mothers on bulletin boards and in newsletters, including links to local motherhood centers, crisis lines, Postpartum Support International, or clinicians who specialize in maternal mental health. First and foremost, be gracious with newly postpartum mothers or mothers of young babies; they are developing rapidly too. Celebrate their accomplishments and milestones as you would celebrate their child’s. Mothers tend to experience early motherhood as both challenging and rewarding, and as such, should be availed of support for their challenges in equal measure to recognition for their accomplishments. |

| Social: As mothers’ priorities shift to be more focused on their baby, their relationships will inevitably change. This can lead to a sense of isolation, though it doesn’t have to. Mothers who find peers who are navigating similar transitions can feel an increased sense of belonging. | Montessori already has a beautiful program that provides practical and social support for new mothers—Montessori parent-infant programs. These classes are a wonderful way for mothers in similar developmental stages to interact with one another and form a supportive social network. Parent-infant classes are also the ideal place for Montessori guides to create an environment that can support mothers as they adapt to new stages of their baby’s development, which inevitably usher in new stages of maternal development. Similarly, supporting parent groups at each level of a Montessori program fosters a sense of community and cohesion for parents, providing critical support as they grow and evolve right alongside their children’s planes of development. |

| Cultural: Respect or lack of respect around a mother’s pathway to motherhood, family structure, or cultural practices can either help or hinder maternal development. | Create a culture of equity and inclusion that respects all family structures, including LGBTQIA+, and is sensitive and respectful to varied methods of child-rearing. This is an opportunity to celebrate the diversity of family structures and child-rearing practices that enrich school communities. Welcome babies at school events, or create systems of support for families with multiple children to facilitate their attendance at school events without being burdened by the need to arrange childcare. |

| Economic: In the United States especially, due to limited family policies, mothers often experience economic setbacks as a result of having a child. Black families are generally disproportionately impacted by lack of paid maternity leave. (Goodman et al., 2021) | Offer scholarships or financial aid, even on a temporary basis, for mothers who are impacted by a lack of leave or “the maternal wage penalty.” (Yu & Kuo, 2024) |

| Physiological: Sleep deprivation, birth injuries, pain, or exhaustion from physical demands of infant care and breastfeeding can impact a mother’s sense of self, physically and psychologically. | Be aware that sleep deprivation and other physical demands of infant care may impact a mother’s day-to-day functioning. Extend compassion and practical support where possible. Small gestures like carrying a car seat or unfolding a stroller for a newly postpartum mother are much appreciated. For mothers of infants and toddlers, sending follow-up emails with details they may forget from a conversation may help them as they navigate sleep deprivation. |

Montessori teacher education programs (TEPs) can begin to incorporate basic matrescence education into their curriculum, particularly for their Infant-Toddler and Early Childhood adult learners, so they can pass on their knowledge to new parents in the same way they pass on their knowledge of a child’s developmental needs based on that child’s plane of development. Matrescence education can be as simple as offering the concept that parents are learning and developing alongside their child and that their development is valued and recognized, just as their child’s development always has been in Montessori settings. “Parenting education would do well to prepare parents for their own developmental needs and to avoid presenting parenthood as ‘all good or all bad,’ but as a stressor, that like any other, can be buffered with proper resources” (Athan, 2020, p. 451). Let us, as Montessorians, be a buffer and a resource for mothers.

A GRIEF-STRICKEN MOTHERHOOD

In Maternal Thinking: Toward a Politics of Peace, feminist philosopher Sara Ruddick writes, “Anyone who commits [themself] to responding to children’s demands, and makes the work of response a considerable part of [their] life, is a mother” (Ruddick, 1995, p. 18). Indeed, by this definition, all Montessori educators could consider themselves mothers. And yet, I would be remiss to write an article about Maria Montessori and maternal development without noting the ways in which Montessori’s own maternal development was thwarted by the social context of her day.

“Anyone who commits [themself] to responding to children’s demands, and makes the work of response a considerable part of [their] life, is a mother.”

In her book The Child Is the Teacher: A Life of Maria Montessori, Cristina De Stefano recounts the circumstances surrounding Montessori giving up her only son, Mario. Montessori and her colleague Giuseppe Montesano, a talented physician in his own right, had a baby out of wedlock. De Stefano writes, “Montessori then faced an impossible choice: She could either marry Montesano, and by doing so give up her career—for in those days women were not allowed to work once they were married—or she would have to renounce her son. There was no alternative” (De Stefano, 2022, p. 42).

Montessori did renounce her son. Still, when a child is born, so too is a mother, and indeed Montessori never stopped being a mother to Mario or to the hundreds of other children whose lives she directly impacted, and to the hundreds of thousands she has indirectly impacted. When Mario was an adolescent and circumstances allowed for a reunion, Montessori and Mario became virtually inseparable. However, due to the still-pervasive social constraints of her time, Montessori referred to Mario as a relative or adopted son, unable to claim him as her biological child. Together, Montessori and Mario went on to form the Association Montessori Internationale, to preserve the integrity of the Montessori Method.

I’ve long found it to be to be one of the central ironies that Montessori, a woman so utterly devoted to children, observing their development with reverence and clear-sighted genius, never truly had the opportunity to observe her own early maternal development and the ways in which its unfolding carries within it a spiritual embryo not dissimilar from what we see in the infant, and a delicate tumult, not dissimilar from what we see in the adolescent. Had Montessori’s circumstances allowed her to experience her own matrescence, perhaps, being the feminist and activist she was, she would have had the courage to look at this phase of life with the same reverence and clear-sighted genius she had for children. Had she not been faced with her impossible choice, which was in actuality a lack of choice, she might have let her gaze fall upon herself long enough to recognize a new plane in the Constructive Rhythm of Life. And perhaps she might have even called her transformation the fifth plane of development.

References

Athan, A. (2020). Reproductive identity: An emerging concept. American Psychologist, 75(4), 445–456.

Athan, A. (2024). A critical need for the concept of matrescence in perinatal psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15: 1364845.

Athan, A., & Carrig, C. (2023, December). Preparing for better outcomes: Matrescence education as a pathway. Postpartum Support International Blog.

Athan, A., & Miller, L. (2005). Spiritual awakening through the motherhood journey. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 7(1), 17–32.

Athan, A., & Reel, H. L. (2015). Maternal psychology: Reflections on the 20th anniversary of Deconstructing Developmental Psychology. Feminism & Psychology, 25(3), 311–325.

Beck, C. T. (1998). The effects of postpartum depression on child development: A meta-analysis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 12(1), 12–20.

Bernardez, T. (2003). The “good enough” environment for “good enough” mothering. In D. Mendell & P. Turrini (Eds.), The inner world of the mother (pp. 299–318). Psychosocial Press.

Burman, E. (1994). Deconstructing developmental psychology. Routledge.

Chzhen, Y., Gromada, A., & Rees, G. (2019). Are the world’s richest countries family friendly? Policy in the OECD and EU. UNICEF Office of Research, Florence.

Conaboy, C. (2022). Mother brain: How neuroscience is rewriting the story of parenthood. Henry Holt & Company.

De Stefano, C. (2022). The child is the teacher: A life of Maria Montessori (G. Conti, Trans.). Other Press.

Dolnick, E. (1998). Madness on the couch: Blaming the victim in the heyday of psychoanalysis. Simon & Schuster.

Goddings, A. L., & Giedd, J. N. (2014). Structural brain development during childhood and adolescence. In M. Gazzaniga & G. Mangun (Eds.), The cognitive neurosciences (pp. 15–22). The MIT Press.

Goodman, J. M., Williams, C., & Dow, W. H. (2021). Racial/ethnic inequities in paid parental leave access. Health Equity, 5(1), 738–749.

Grazzini, C. (1996). The four planes of development. NAMTA Journal, 21(2), 208–241.

Gunja, M. Z., Gumas, E. D., Masitha, R., & Zephyrin, L. C. (2024, June). Insights into the U.S. maternal mortality crisis: An international comparison. The Commonwealth Fund.

Kozhimannil, K. B., Trinacty, C. M., Busch, A. B., Huskamp, H. A., & Adams A. S. (2011, June). Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum depression care among low-income women. Psychiatric Services, 62(6), 619–625.

Montessori, M. (1972). The secret of childhood. Ballantine Books.

Montessori, M. (1995). The absorbent mind. Henry Holt.

Montessori, M. (2012). The 1946 London lectures. Montessori-Pierson.

Montessori, M. (2019). Education and Peace (Vol. 10). Montessori-Pierson.

Montessori, M. (2019). To Educate the Human Potential. Aakar Books.

Montessori, M. (2020). The Child in the Family (Vol. 8). Montessori-Pierson.

Murthy, V. (2024, August 28). Surgeon General: Parents are at their wits’ end. We can do better. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/28/opinion/surgeon-general-stress-parents.html

Orchard, E. R., Rutherford, H. J. V., Holmes, A. J., & Jamadar, S. D. (2023). Matrescence: Lifetime impact of motherhood on cognition and the brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 27(3), 302–316.

Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2022). Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. StatPearls Publishing.

Paradice, K. (1995). Postnatal depression: A normal response to motherhood? British Journal of Midwifery, 3: 632–635.

Pawluski, J. L., Hoekzema, E., Leuner, B., & Lonstein, J. S. (2022). Less can be more: Fine tuning the maternal brain. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 133: 104475.

Raphael, D. (1975). Matrescence, becoming a mother, a “new/old” rite de passage. In D. Raphael (Ed.), Being female: Reproduction, power, and change (pp. 65–71). Mouton.

Rubin, R. (1984). Maternal identity and the maternal experience. Springer.

Ruddick, S. (1995). Maternal thinking: Toward a politics of peace. Beacon Press.

Thurer, S. (1993). Changing conceptions of the good mother in psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Review, 80(4), 519.

Trivedi, A. J. (2019, June). Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs—Theory of Human Motivation. International Journal of Research in All Subjects in Multi Languages, 7(6).

Winson, N. (2017). Transition to motherhood. In C. Squire (Ed.), The social context of birth (3rd ed., pp. 141–155). Routledge.

Yu, W., & Kuo, J. C-L. (2024). Research note: New evidence on the motherhood wage penalty. Demography, 61(2), 231–250.