I stumbled onto Montessori when my first son was born and I was given a copy of Paula Polk Lillard’s Montessori from the Start. I was a committed Montessori parent, trying my best to create a Montessori-inspired home environment; I was also innately techno-suspicious—our home was filled with wooden objects, we had a “no batteries” rule for gifts, and my children didn’t engage with screens at home. However, some of my friends (and my negotiating 6-year-old son, whose classmates were watching movies and playing video games) warned me that keeping kids off technology for so long would set them behind their peers and leave them out of touch. I put that argument to the teachers at my children’s excellent Montessori school, who clarified that starting at the Elementary level, students engaged in limited computer use. But mostly, their response went something like this: “Given how much

technology there is in children’s lives outside of school, we don’t think they are going to be technology-deprived, and there are huge advantages to the materials and methods Montessori developed and that we focus on here.” This viewpoint represents one common approach to thinking about technology in the classroom. Several Montessori teachers I’ve known outsource technological education to the broader culture, while staying focused in the classroom on the faithful use of Montessori’s own materials and methods, which have proven themselves, over more than 100 years and all around the world, to enrich children’s lives and foster their development.

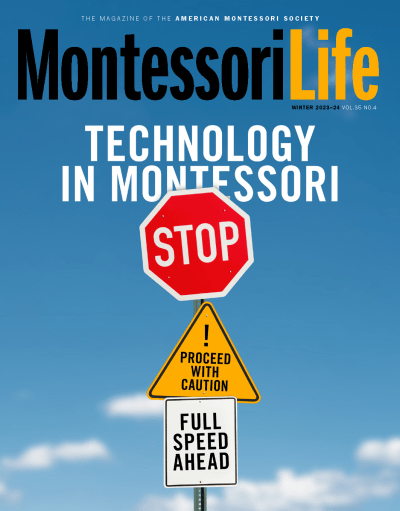

This article was featured in our 2024 Winter edition of Montessori Life magazine. Read the full issue online (AMS members only).

AMS members also receive a print subscription to Montessori Life magazine. Become a member today to receive your own subscription plus access to the complete digital archives.

Another approach to technology in the classroom is expressed in an excellent article I entitled “Technology and Its Use in a Montessori Environment” by John McNamara, a longtime Montessori educator who trained in Bergamo with a close collaborator of Mario Montessori. McNamara (2020, pg. 224) begins the article by clarifying the overarching goal for any Montessori educator:

Our goal in a Montessori school is a child who is educated for life. We want to help the child to become a fully functioning human being adapted to his time and place, to become a mature, confident adult, free from anxiety and fear.

McNamara writes about the benefits of traditional Montessori materials for fostering the mind-body connections essential for children’s development, and he rightly warns about the dangers of technology that derails active, prolonged attention through offering quick solutions. In a 1923 lecture (pg. 6), Montessori herself expressed this same idea:

It is not our purpose that the child should learn at an earlier age or in a shorter time. In fact, we try to eliminate some of the aids which might lead to this more

rapid learning, in order that the child’s inner forces and energies may have more time to develop and to strengthen themselves.

McNamara emphasizes how Montessori fundamentals remain applicable regardless of what technologies one might introduce into the classroom. His basic framework embodies a careful and reflective affirmation of technology: “Technology becomes a means, not an end. A real key is balance. We would be foolish to ignore existing and developing technologies and we would be just as foolish to abandon all that we are doing now” (2020, pg. 227). (I read “all we are doing now” to mean the wide range of Montessori materials and methods that do not involve the latest technologies.)

Pushing against the unreflective obsession in our culture—and in many (non-Montessori) schools—for the latest gadgets, McNamara reminds us to focus on the purpose of all that technology, which, for him, is to support the “unchanging basic needs of the child” (pg. 229). At the same time, in contrast to my own knee-jerk technophobia, he encourages us to make use of technology to support those needs.

In one way, of course, children’s basic needs are unchanging. As I’ve argued in a couple of recent books on Montessori’s philosophy (Frierson, 2020 and 2022), all children need to exercise certain basic intellectual virtues. All children need to express their character, and cultivate respect for others, and practice social solidarity. All children need food and love and activities that interest them. In another sense, however, human children are unique among animals in that their basic needs are constructed in relation to their environments. Montessori wrote, “Man does not have a precise heredity to do one special thing…. he is not obliged to do just one thing…. [E]very man must prepare in himself an adaptation that is not hereditary. He must prepare his own adaptation” (2012, pg. 91).

Even at the basic muscular level, “the muscles of man are not directed just by instinct, as are those of other creatures. The individual himself must animate his motor powers… [to]… prepare for his own individuality” (Montessori, 2016, pg. 95). It is not a basic need of children as such to read, or write, or do arithmetic. For much of human history, children did none of those things. Being able to tie a shoelace or put on a jacket is not a basic need, but one born of a particular set of cultural practices. Moreover, all of these needs—reading, writing, math, and every particular activity of Practical Life—all of these are ultimately needs for fluency in particular technologies. Unlike other animals, humans are essentially technological creatures. The child’s absorbent mind is precisely their capacity for absorbing proficiencies in the technologies that define their environment.

It is easy to think that “technology” refers to computers or microscopes or the latest gadget. But insofar as a technology is something human beings make in order to enhance our abilities, language itself is a technology, and writing is a technology that itself depends upon subsidiary technologies. Many Montessori materials are specifically organized in order to cultivate the bodily skills needed to make use of the pencil (or pen) and paper, which were the primary writing technologies of the early twentieth century. Writing provides an excellent example of how Montessori viewed technology in the classroom; for her, writing was not merely a means to other ends. Rather, Montessori saw the capacity for children to write (and read) as itself one of the more important ends of education (at least, of early education). Of course, children will use reading and writing for other ends; writing helps them do mathematics. But writing is neither a mere means towards other more basic needs nor is it a “basic” need of children in all times and places. Learning to write is an essential part of the adaptation of children to an environment defined, in part, by the technology of writing.

One of Montessori’s most important pedagogical principles is that of “indirect preparation.” Many of the early materials in Montessori classrooms cultivate the skills—especially the physical skills—needed to write well. Cylinder Blocks have pencil-sized grips so that children build the muscular memory, dexterity, and strength to use pencils and other writing implements well. Sandpaper Letters not only associate visual symbols with sounds but also support the proprioceptive, tactile, and motor awareness to write well. What is striking about these examples, and about much in the Montessori classroom, is the extent to which the effective use of technology is an explicit goal of indirect education. While McNamara emphasizes how technology can be used to foster other sorts of goods, Montessori indirect preparation often makes use of children’s innate needs and interests as means for cultivating fluency in the use of technology. It can be easy to forget that books and pencils (and paintbrushes and musical instruments) are technologies. Along with spoken language, they were the dominant technologies of communication in Montessori’s day.

Once we see books and pencils and even language itself as technologies, however, it’s clear that technology is not merely a means, but also one of the primary ends, of education. That is, Montessori educators should see as one of their primary missions the task of equipping children to make effective use of the technologies available in their cultures. The “explosion into writing” that was so striking in Montessori’s first Children’s House was a manifestation of just such a technological fluency.

The technologies that children must grow up to use well are not limited to pencils and paper—both then and now. In The Advanced Montessori Method, Vol. II (2020, pg. 5), Montessori described various materials she employed in her (particularly Elementary) classrooms, including a Movable Alphabet where letters are in cursive and punctuation marks are included, and the letters are printed in three colors (red, black, and white), with 20 copies of each letter in each color. Only in the Italian edition of this work (2018, pg. 268), she then adds an intriguing footnote:

Other copies bear letters of the alphabet according to the shape of the printout, and are arranged in the filing cabinet according to the order in which the letters of the alphabet are in typewriters.*

In Montessori’s envisioned Elementary classroom, the Movable Alphabet would not only provide children with an opportunity to form words and sentences, but would also indirectly prepare them for using typewriters by giving them a kinesthetic understanding of the position of keys on a typewriter. Montessori’s suggestion here is consistent with her general emphasis on indirect preparation, and here, a child interested in composing words and sentences—and perhaps even in copying them with pencil and paper—indirectly prepares to use a typewriter (or computer, or anything with a QWERTY keyboard).

Montessori lived in a world of rapid technological expansion, and she rightly saw that that technological expansion would only increase in pace. She also warned about the crisis that would come if human beings did not learn to make use of the technologies available to them, and she insisted on the importance of learning to master those technologies rather than being mastered by them. For her, however, technological expansion was not a dystopia to be avoided but a cosmic task for humans to carry out, one that could be done badly—with all the divisiveness, depression, anxiety, oppression, and violence that technology can cause—or could be done well—as a source for improved human lives, global unity, and the improvement of the planet itself. “The secret,” wrote Montessori, “is this: making it possible for man to become the master of the mechanical environment that oppresses him today” (2015, pg. 27).

In itself, technology is neither a danger to be feared nor a mere means to meet children’s developmental needs. Proficiency in emerging technologies is one of the most pressing needs that children have. Montessori was a master of indirect preparation, and she indirectly prepared children of her day to master the technologies of her day. The technologies that today’s children must eventually master are different, of course—children today should know not merely how to write, but how to program a computer. They may need to know how to drive a car, send a text message, use Google search strings, create TikToks or other video content (and also how to engage with such content intelligently), and ask ChatGPT the right kinds of questions (and vet the answers). These are all technologies that are part of the world today’s children inhabit, and proficient use of them is part of the adaptation to environment that the absorbent mind seeks. But today’s children are also growing up in an environment that overwhelms them with technology in a disordered and chaotic way, and which fosters passive consumption of and submission to technology rather than able use of it.

Montessorians, with their long history of careful attention to children’s developmental possibilities, can and should develop materials and pedagogical methods that can help children not merely use but master the technologies of the future. This does not mean putting a computer in the hands of every 3-year-old; quite the contrary. (Montessori did not even put pencils and paper in the hands of 3-year-olds until they had the physical and psychological preparation to use those materials well.) Rather, it means thinking carefully about what materials can be of direct interest to children while at the same time indirectly preparing the physical, sensorial, and cognitive skills they will need to navigate the technological world in which they live. I suspect that pianos and other “keyboards” could be an important indirect preparation. The Vision Board (see page 28) is an excellent example of a creative Montessori material for preparing keyboard literacy. There are no doubt countless others that conscientious teachers have already developed for their students. I look forward to a Montessori world where teachers respond to “How will my child be up to speed on technology?” in the same way they respond to “How will my child learn the math they need to know?”—namely with a tour through the rich and beautiful objects and lessons that prepare students to thrive in our world.

Suggested Reading

Douglas Rushkoff’s Program or Be Programmed (Soft Skull Press, 2011) is an easy-to-read manifesto on the importance of technological literacy, including some principles to avoid being controlled by computing and internet technologies.

References

Frierson, P. (2020). Intellectual agency and virtue epistemology: A Montessori perspective. Bloomsbury Academic.

Frierson, P. (2022). The moral philosophy of Maria Montessori: Agency and ethical life. Bloomsbury Academic.

McNamara, J. (2020). Technology and its use in a Montessori environment. The AMI Journal 2020, pp. 224–232.

Montessori, M. (1923, May 15). “Lecture 15.” Standing Archives, Seattle University, Seattle, WA.

Montessori, M. (2012). The 1946 London lectures. Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company, pg. 91.

Montessori, M. (2015). Education and peace. Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company, pg. 27.

Montessori, M. (2016). The child, society, and the world. Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company, pg. 95.

Montessori, M. (2018). Opere. Garzanti s.r.l., p. 268. Retrieved from a.co/2Amc9g4.

Montessori, M. (2020). The advanced Montessori method, vol. II. Montessori-Pierson Publishing Company.

About the Author

|

Patrick Frierson (he/him) is a parent of three and the Paul Piggott and William M. Allen Professor of Ethics and Philosophy at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. He has written several academic articles and two recent books on Montessori’s philosophy and is currently finishing a new book, The Philosophy of Maria Montessori, for Oxford University Press. Contact him at frierspr@whitman.edu. |

Interested in writing a guest post for our blog? Let us know!

The opinions expressed in Montessori Life are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of AMS.