Due to the steady growth of Montessori in the public sector over the past 20 years, the question of whether authentic Montessori can be implemented in public schools is often raised. To try to shed light on this question, in 2011, we began a research study of more than 315 South Carolina public school classrooms (with approximately 7,500 students).

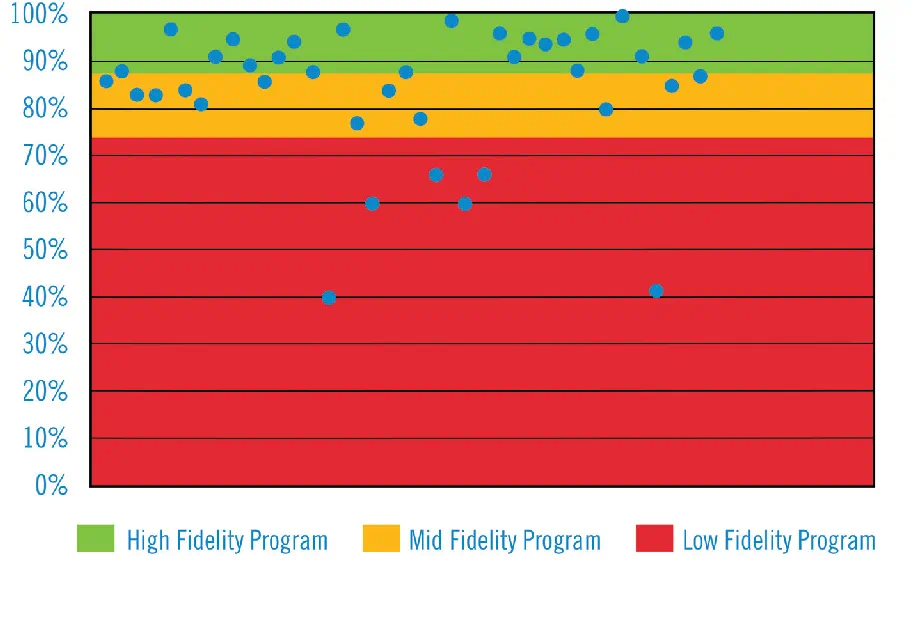

It is our belief that a public school Montessori program, if it satisfies the five “Core Components of Montessori Education” listed below, can have high levels of authenticity, even with the challenges inherent in the constructs of traditional education. In a public setting, we like to say we are “swimming against the tide,” since some of Montessori’s essential practices are just not the norm in traditional schools. For example, 3-year multiage groupings, a long uninterrupted work period, and a curriculum that is not outwardly and solely standards-based are qualities not commonly seen in traditional public school classrooms. Despite the challenges of implementing in the public arena, we discovered that the majority of Montessori public school programs in South Carolina were implementing Montessori with either high or midlevel authenticity.

Core Components of Montessori Education

“While there are many components that are integral to quality Montessori implementation, the American Montessori Society recognizes 5 core components as essential in Montessori schools—properly trained Montessori teachers, multiage classrooms, use of Montessori materials, child-directed work, and uninterrupted work periods. Fully integrating all of them should be a goal for all Montessori schools.”(For more specifics, see amshq.org/corecomponents.)

Levels of Montessori Program Fidelity

Determining the authenticity, or fidelity, of the 42 programs included in our research involved extensive time and funding. Trained and credentialed observers visited 120 randomly selected Montessori public school classrooms across the state for 1-hour observations, to assess the classroom environment. These observations were followed by 30-minute interviews with teachers to explore lesson planning, recordkeeping, and assessment practices. In addition to the rich data gleaned from classroom visits and interviews, teachers and principals provided additional input and perspective through in-depth surveys.

In addition to assessing program or practice impact, many research studies have a goal of translating findings into action steps for improving education. We shared this goal. As researchers, we strongly believed we would be failing if we only provided data on outcomes as a part of conducting a study as comprehensive as this one. What a huge missed opportunity it would be to not be able to share with practitioners the useful implementation data and resulting actionable findings!

We have finished the job of collecting data and organizing it in a summarized format that we hope will be understandable and useful to practitioners. But our job is not complete. It is an equally important task to share the information collected and compiled as widely as possible and to make sure it gets into the hands of practitioners who can fully use the data to make Montessori in public schools the best it can be. This article is one way we are hoping to get the information out to as many Montessorians as possible.

In this article, we will discuss the barriers to implementation of Montessori in public schools that emerged from the study, some of which likely will not be a big surprise to practitioners. We will follow each barrier with a discussion of actionable items and recommendations for addressing these barriers. While our study focused only on South Carolina, it is safe to assume that at least some of these issues, and probably others, exist in other states as well. Because we are focusing on challenges and barriers, it may give the impression that the overall study findings were negative. On the contrary: Overall findings were very positive when examining academic and behavioral outcomes of Montessori students as compared to their traditional counterparts. In addition, survey data revealed that the vast majority of South Carolina’s public school Montessori teachers are very satisfied with their jobs and plan to continue in their roles as teachers, a situation very different from national statistics that consistently indicate low levels of teacher job satisfaction and retention.

Barriers To Implementation Of Montessori In Public Schools

A Lack Of Knowledge About The Basics Of Montessori Philosophy And Method On The Part Of Principals And/Or Other School District Administrators

In South Carolina, there is an approximate 30% rate of annual principal turnover and also fairly high district-administration turnover, yielding a situation where schools with Montessori programs frequently have new administrators. Exacerbating this problem is that very few Montessori teachers in South Carolina express interest in moving into administrative positions, reducing the pool of potential administrators qualified to run a Montessori program. Thus, few hired principals that come into Montessori schools have Montessori credentials or experience in Montessori classrooms or schools. Making this problem even more challenging is the fact that there are limited options beyond one-to-one training that can equip non-trained principals with Montessori basics as they begin their leadership role.

Problem: Principals need experience with or basic knowledge of Montessori to be able to support authentic Montessori and make necessary program accommodations at school and district levels. Only 23% of teachers reported their principals have basic knowledge of Montessori philosophy. Just 14% of principals reported having Montessori teaching certification, while only 8% have Montessori administrator certification. However, all principals reported attending one or more Montessori-focused professional development sessions.

Result: Because they may not fully understand the model, administrators can make decisions that inhibit authentic Montessori implementation, oftentimes without even realizing they are doing so or understanding the implications. This can result in mandating practices that are antithetical to Montessori, such as mandatory letter grades, student behavior reward programs, and assessment that does not value classroom observation or feedback. In addition, the lack of knowledge does not give them the ability to justify how things are done in Montessori and makes them more likely to succumb to pressure to accommodate new district initiatives that may not align with Montessori.

Potential Solutions:

- Offer more professional development and training certificates.

- Provide funds for Montessori administrators to enter a training program offering a Montessori Administrative credential.

- Offer a user-friendly and low cost online course on the basics of Montessori.

- Expand recruitment of administrators with Montessori backgrounds.

- Advertise searches nationally, emphasizing Montessori.

- For non-trained hires, make contracts renewable only if Montessori training is pursued the first year in the administrative position.

- Provide more opportunities for networking/mentoring.

- Form online groups for Montessori public school principals.

- Assign experienced Montessori principals to mentor new Montessori principals.

- Conduct periodic, regional meetings of Montessori administrators for networking and idea sharing.

The Emphasis On State Standards Versus Following The Montessori Curriculum

While most South Carolina public Montessori teachers agreed that they were able to implement authentic Montessori while incorporating state standards, and over three-quarters of teachers reported using the Montessori curriculum/sequence training as their foremost teaching guide, nearly half of all teachers reported that their schools required them to use a pacing guide for following standards and benchmark testing.

Problem: When teachers use a curriculum guide other than Montessori, it dilutes the focus on the Montessori teaching and philosophy. In addition, when administrators do not support the use of the Montessori curriculum as the sole guide for teachers, as is the case in many classrooms, it undermines teachers’ abilities to do what they were trained to do and to effectively teach in the manner they were taught.

Result: Not allowing teachers to teach in the way they were trained and with the corresponding curriculum leads to diluted delivery of Montessori, teacher frustration, less effective teaching, and fewer benefits of a deeper/broader curriculum with emphasis on affective skills.

Potential Solutions:

- Increase opportunities for communication between Montessori teachers and administration (e.g., have a regular schedule of monthly meetings to:

- Keep lines of communication open

- Discuss matters related to curriculum, standards, testing, etc.)

- Educate administration on how standards are incorporated within Montessori curriculum/lessons.

Obtain a correlation of the standards and Montessori and review with principal (your state Montessori association or local Montessori public school may have information on correlations done in your state).

- Use Montessori materials in explaining the correlation.

- Show examples of how Montessori curriculum goes well beyond standards.

- Explain how a pacing guide (for whole-class instruction) is not compatible with self-paced, individualized instruction.

- Discuss how curriculum “lay overs” or strategies mandated by district or school are not compatible with Montessori. Stress that Montessori is a complete curriculum, and its authenticity is diminished when other curriculum strategies take precedence.

A Focus On Testing And The Amount Of Testing Required By The District And State

Approximately 80% of South Carolina’s Montessori principals reported that they focused on preparation for state-mandated testing in their classrooms, and teachers cited testing requirements as the most common reason for modification of the Montessori curriculum. In addition, principals reported that state-mandated assessments compromise the character of the Montessori program.

Problem: At the Early Childhood level, district-mandated testing can remove the teacher from the classroom for up to 2 weeks at the start of school year, and some tests are given one-to-one up to three times per year. This problem exists at other levels as well. In addition, there is the added problem of testing in a multiage classroom, as three different groups taken out of class at different times is a disruption to instruction and hinders appropriate multiage student groupings.

Result: Teachers are losing large amounts of time for instruction and are frustrated at having to focus on testing rather than authentic Montessori teaching and assessment. In addition, there is less time for proper implementation of key components of Montessori, such as uninterrupted work time and children learning from peers of different ages.

Potential Solutions:

- Educate administrators on how assessment of mastery is measured in Montessori.

- Explain how observing a student mastering a skill is authentic assessment in its highest form.

- Show examples of student record-keeping, whether done manually or using a commercial software program.

- Educate administrators on the importance of self-paced curriculum and “following the child.”

- Explain how respecting the child includes honoring each child’s unique path of learning.

- Assure administrators that Montessori teachers are knowledgeable about what standards a child is expected to meet at each age level. While they don’t “push” children, they are aware of age-level benchmarks.

- Assure administrators that “following the child” does not take the place of following the sequence of lessons; instead, teachers expect each child to put forth his best effort and be accountable for use of time and quality of work.

- Ensure proper environment and culture around testing.

- In the cooperative (vs. competitive) Montessori Method, children are not tested to assess mastery.

- This does not prevent students from having “spelling checks” on weekly words for study or memorizing math facts when they understand the concept of each order of operations.

- Rubrics are used as an assessment tool.

- Recognizing that testing in public schools is not going away, discuss ways that Montessori students are being prepared for such tests.

- Include in work plans daily reading of passages and answering comprehension questions in a multiple choice or open-ended format.

- Emphasize translating lessons in computation (Stamp Game, Bead Frame, etc.) into applied situations (word problems).

- Include alternate ways of representation of number concepts (e.g., in addition to “ten” being represented by the ten-bead bar, introduce various arrays that show ten).

- Negotiate amount and method of testing.

- Since benchmark testing is based on pacing guides, ask that the benchmark be taken just once, at the end of year, for a “grade level” assessment.

- Let students take MAP testing in the classroom (i.e., students do MAP on a classroom computer as part of their work plan vs. groups of students by grade level going to a computer lab, since the latter can be very disruptive in a multiage class).

- Use the actual rubric used for scoring standardized writing tests when assessing essays throughout the year and help students become familiar with the content of the rubric.

- For the Early Childhood level, decrease tests that require one-to-one administration multiple times a year/brainstorm ways for the teacher to stay in the classroom, especially in the beginning of the year.

The Pressure To Use Extrinsic Rewards, Especially In Schools With Both Montessori And Non-Montessori Classes

In Montessori classes, students work and learn at their own level and pace. They are motivated to learn, unless that desire is hampered by boredom or frustration by work that is not at their level. Since instruction is individualized in Montessori, students experience the joy of learning as they work each day. Much of what is learned is by discovery, using hands-on materials. Montessori students like school! Learning is its own reward. Children do not have to be goaded to learn or offered a concrete reward for mastery of skills or good behavior.

Problem: Since the incorporation of behavior modification in schools in the 1980s, rewards have been viewed as a way to get students to do their work and also behave. Extrinsic rewards in the forms of candy, toys, play money, stickers, honor roll, and the like now exist in most public schools. In Montessori schools, classes capitalize on the intrinsic reward of learning, and extrinsic rewards are not part of the school culture. Even though parents are told before they make the Montessori choice that there will not be an honor roll or a similar rewards programs, this practice is still sometimes confusing for them. Avoiding extrinsic rewards also is somewhat more difficult in school-within-a-school programs, because traditional classes in the school are likely to use these rewards. But efforts must be made to diminish or eliminate them in schools with Montessori programs.

Result: The goal of fostering the joy of learning for its own sake is compromised when extrinsic rewards are used in Montessori classes. A Montessori teacher struggling with classroom management may resort to extrinsic rewards as a way to improve behavior and work habits. Oftentimes, when a schoolwide program of rewards exists, Montessori teachers are questioned and told that they must participate in the schoolwide program because they are part of the school. Even in all-Montessori schools, other staff need to understand the practice of not using extrinsic rewards. For example, sometimes a music or PE teacher, media specialist, or cafeteria worker will give children treats, stickers, or a sign to place on their door—for example, “PE Class of the Week”—for good behavior. This practice compromises the authenticity of the Montessori program.

Potential Solutions: First and foremost, all staff working with Montessori students must fully understand the Montessori practice of not using extrinsic rewards. This expectation needs to be stated clearly by administration, with follow-ups/reminders happening throughout the year. Montessori teachers can explain to staff and administration that Montessori students for 100 years have shown they will work hard without extrinsic rewards. They don’t need them! In fact, research has shown that extrinsic rewards can be harmful to students in the long run (thinking they have to get something if they work hard or behave well). Two good resources for this are Punished by Rewards by Alfie Kohn and Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius by Angeline Lillard.

The Inability Of Schools To Be Released Or Exempted From State Or District Regulations In Order To Implement Practices Aligned With Montessori

While most principals reported that the district allows for some flexibility in school and district requirements, there are still mandates from districts and the state that conflict with Montessori practice and philosophy. For example, in addition to the testing requirements already discussed, many Montessori principals report that their schools are required to use numerical or letter grades, and many are still using the same report cards traditional schools use.

Problem: Authenticity of a program is diminished when a school asks Montessori students to get letter or number grades rather than focus on mastery. This is a serious break from the Montessori philosophy of non-competitiveness and affirmation of students working at their own pace vs. “keeping up” with classmates.

Result: Teachers become demoralized, because the philosophy they believe in, and have been trained in, is being compromised. They are confused as to how to come up with a letter grade—what do they average to get one? In addition, parents made the Montessori choice expecting it to be a continuous progress program, with assessment by observation, and thus may question this change in policy. Students are primed to compare their scores to other students simply because of human nature and the fact that there is something to compare.

Potential Solutions: Schools must be given the ability to create and use a non-graded Montessori report card that blends standards-based and Montessori language and terms. The ratings should be reflective of continuous progress (e.g., mastered, learning, needs more time).

- Educate the principal and other staff about the non-competitiveness of the Montessori Method.

- Review how grades naturally cause student comparisons or rankings.

- Explain how authentic assessment through observation, rubrics, and the like is a valid form of assessment that truly lets the teacher, parent, and child know what has been mastered.

- Emphasize that, in individualized instruction, students are working on different skills/content/concepts at different rates of speed. Traditional grading is geared toward whole-group instruction, after which the whole class takes the same test. Mention that many districts have switched to no letter grades through third or even sixth grade for all students in the district.

- Develop an alternate Montessori progress report or report card.

- Show samples of other Montessori report cards.

- Explain which schools have been using them and for how long.

- State that the absence of grades does not usually cause parent complaints—in fact, it is just the opposite, because parents know exactly where their child is in every subject area. At conferences, parents are shown records of the student’s work and progress—which offers them much more than a “B” or an 83% conveys.

- If the principal/district mandates a graded report card, attempt the following until there is a better understanding of Montessori assessment:

- Do not use grades in public for students to see, but find ways to estimate a grade on work in each subject area.

- Rubrics can easily be converted. Many teachers ask students to state what they would like to aim for on the work—for example, 10 out of 12 indicators on a rubric.

- Share the estimated grades and rubrics with students and parents.

We hope the information presented here is helpful to educators who seek to implement authentic Montessori in a setting that typically presents challenges to many of the core Montessori practices. We have seen over and over that it is possible for public schools to implement authentic Montessori, even considering these challenges, and how much students in these schools benefit. It is important that we don’t shy away from these challenges and meet them head on, so we can bring Montessori to as many students as possible.